Energy projects target Wiscasset | Will Wiscasset undergo an energy renaissance?

A quiet dirt road in Wiscasset leads to the site of what was once the state’s sole nuclear power plant. As Route 144 peters out along the former Maine Yankee site, “No trespassing” signs pop up like weeds along the road’s shoulder, warning passers-by that “force will be used if necessary” against unauthorized visitors. Decommissioned for more than a decade now, the site remains home to a cluster of concrete casks holding spent nuclear fuel that sit atop a hill overlooking the Back River. The once-familiar domed nuclear reactor is gone, toppled by explosives in 2004. The only other major infrastructure left is an electrical switchyard, which still buzzes with power and could prove key to the site’s rebirth.

Toronto developer Riverbank Power Co. is considering building a $2 billion underground hydropower station at the site that could become the largest development of any kind in Maine’s history. The system, called an Aquabank, would feed 1,000 megawatts of energy — enough to power 300,000 homes — through the switchyard and onto the local power grid. Asked to describe the scale of the project, Dana Murch, a hydropower specialist for the Maine Department of Environmental Protection, chuckled before answering. “The scope is truly gargantuan,” he said. “If this project were built, at 1,000 megawatts, it would be, all by itself, bigger by almost a third than all of the hydropower generation in Maine combined.”

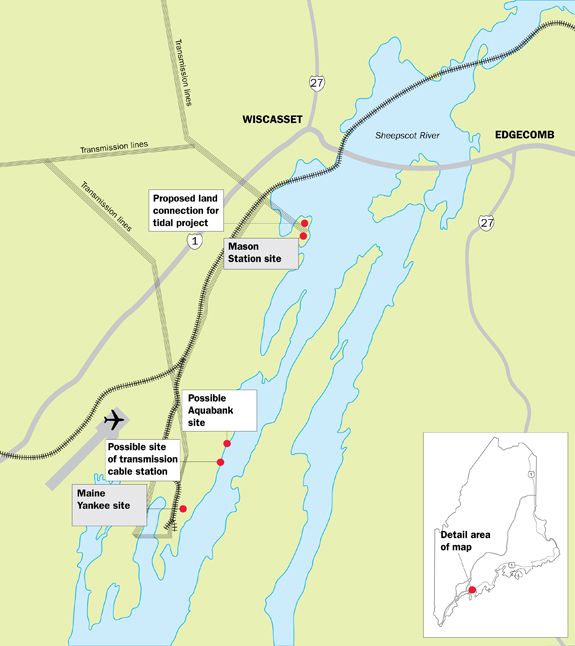

Though easily the largest, Aquabank isn’t the only ocean energy project eyed for Wiscasset. Transmission Developers Inc., another Toronto company, wants to bury a high-voltage cable 3 feet under the sea floor that would transport to Boston renewable energy generated in Maine. The $1 billion project would essentially treat the state’s excess energy as an export crop to meet demand in urban markets. A third and smaller project, rising out of a partnership between the Midcoast town and a local conservation group, would funnel tidal currents in the Back River through turbines for distribution to the local power grid.

While the projects remain conceptual — actual construction is at least several years out — the convergence of three ocean energy proposals in Wiscasset is hard to dismiss. The activity could mark the beginning of the town’s renaissance as an energy hub. Or, with lingering controversy over a failed bid for a coal-gasification plant, proposals could generate more talk than megawatts. But Wiscasset’s history as an energy town — its institutional knowledge, power and rail infrastructure, and proximity to water resources — is undeniably attractive to developers. A viable replacement to the gaping hole Maine Yankee left in Wiscasset’s tax base would be hard to pass up.

Aquabank

• Who: Riverbank Power Co.

• What: Aquabank underground hydro station

• Cost: $2 billion

Riverbank Power is considering Wiscasset among a dozen or so contenders for five Aquabank sites in North America. The system has never before been built. “I can’t go anywhere in the world and look at studies of what the impacts are,” Murch of the DEP said. Hundreds of pump-storage facilities exist all over the world, but all use surface reservoirs. “Nobody has taken an above-ground reservoir and put it underground,” said Riverbank founder and CEO John Douglas. “That’s our innovation.”

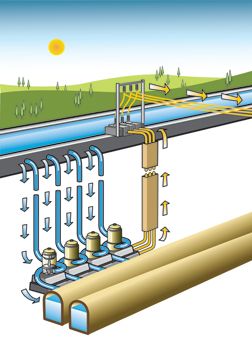

This is how Aquabank works: Water drawn during the day from the Back River, a tidal estuary of the Atlantic Ocean, would rush 2,000 feet down four chutes to a 100-acre underground facility dug into the bedrock. The water would then flow through a series of three-story-tall turbines, generating power that would be sent through a transformer and back up cables to a switchyard at the river’s edge for distribution to the local grid. Meanwhile, the water would rest in several cavernous underground storage tanks, each capable of holding more than one billion gallons.

The system would operate in six-hour bursts and generate an astounding 1,000 megawatts of power, more than Maine Yankee at its peak. Aquabank’s most obvious advantage is that the system can accommodate energy demand. Power is generated and sold during the day, when demand and prices are high. At night, the whole system kicks into reverse, pumping water stored in the reservoirs back into the river using power generated elsewhere in Maine. The cost for that power is low, which means that even though the system ultimately uses more electricity than it generates, the company turns a profit by selling power for more than it costs to buy it. So no new energy would be added to the state’s portfolio. But renewable energy could be stored and used when it’s needed, unlike wind power, which generates electricity only when the breezes blow.

Riverbank plans to buy Maine-generated wind and other renewable power at night, so the whole process is free of fossil fuels, said Douglas, who in 2003 founded the wind power company Ventus Energy. He sold it in 2007 for a reported $124 million. In Wiscasset, he’s spoken with lobstermen, scallop fishermen, environmentalists and others about the plan, which he’s confident wouldn’t hamper traditional industries or the aquatic environment. Extensive feasibility studies, if Wiscasset is chosen, will back him up, Douglas said. Local and state support, the site’s excellent geology and hydrology, and its proximity to the Maine Yankee substation and another at the defunct Mason Station power plant all have proved attractive, he said. “Wiscasset is one of our top prospects, for sure.”

After a two- to three-year permitting phase, construction would take at least four years and employ about 1,000 people. Once operational, Aquabank would bring 50 to 100 permanent jobs to the area, a far cry from the 800 Maine Yankee employed. The near-passage of a bid for a coal-gasification plant on the Maine Yankee site testifies to the community’s readiness for new jobs, Douglas said. Residents in 2007 rejected several zoning measures key to the $1.5 billion project by a vote of 868-707. Unlike that plan, Aquabank’s surface presence is limited to a roughly 2,000-square-foot structure. “This is a renewable energy project that seems to have garnered more interest and more curiosity,” Douglas said.

Transmission cable

• Who: Transmission Developers Inc.

• What: High-voltage DC cable

• Cost: $1 billion

In Riverbank’s same office suite in Toronto, another company is eyeing plans for ocean energy development in Wiscasset. Transmission Developers Inc. is fleshing out plans for its first publicly announced project: a $1 billion undersea power cord that would stretch from the town to Boston. Two 6-inch cables buried in the river bed would shuttle up to 1,000 megawatts of excess power generated by Maine’s growing renewable energy sector to urban markets in need of power. The AC currents would be converted to DC currents, which are better suited to use in waterway cables. A three-acre converter station, possibly on Maine Yankee property, would be the only evidence of the project above ground.

The cable, and Aquabank, could help Maine realize Gov. John Baldacci’s goal of generating 3,000 megawatts of new wind power by 2020. The cable technology has been used before, including a 65-mile cable from New Jersey to Long Island, N.Y., and a 150-mile line connecting Norway and the Netherlands. In a unique arrangement, customers would sign up to ship power on TDI’s cable. With traditional transmissions, costs are pooled and users in the New England power pool pick up the tab.

TDI’s project could conceivably transport power generated by the Aquabank, but both Douglas, a majority shareholder in TDI, and TDI President Donald Jessome stressed that the projects are separate. Financial models and sustainability studies are being developed on each as a standalone project, Douglas said. New York City investment firm BlackRock, which managed $1.31 trillion in assets as of Dec. 31 according to its website, is a primary investor in both developments.

“Show me the money,” said a skeptical Ray Shadis, an Edgecomb resident who worked with a grassroots group to shut down Maine Yankee. Wiscasset has seen energy proposals come and go, often stymied by difficulties obtaining financing, a particularly tough feat in today’s credit market, he said. Jessome countered that actual project financing won’t kick into gear for a couple more years, when more favorable credit conditions will likely arise. Setting aside potential environmental problems, Shadis acknowledges that a viable energy storage project that could level alternative energy along the coast would be beneficial. “The risk now is that Wiscasset pins its hopes on one or two large projects, which may or may not materialize, when the town really needs to look at how it’s going to invest in jobs in multiple sources on a smaller scale,” he said.

Tidal project

Who: Town of Wiscasset, Chewonki Foundation

What: Tidal project

Cost: $1 million - $2million for studies

Peter Arnold’s finger hovers over a map hanging in the Chewonki Foundation’s conference room as he describes what he hopes will become the third element of Wiscasset’s energy renaissance. Arnold, the conservation organization’s sustainability coordinator, points to the study area for a tidal energy project he’s managing in partnership with the town. His measured speaking manner quickens as he ponders the confluence of his, Riverbank’s and TDI’s projects in Wiscasset. “There’s an opportunity for Wiscasset to think of itself again as an energy town,” he said. “Only this time it’ll be a renewable energy town.” While located in the same waterway, each of the three projects capitalizes on a different resource niche within it, Arnold said. “They’re all synergistic. There’s no conflict at all.”

The town/Chewonki project, preliminarily green-lighted by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, would harness the rise and fall of tidal waters through turbines in the Sheepscot River. Total generating capacity would range from one to 10 megawatts, and costs for studies and permitting are estimated in the $1 million to $2 million range. The number and location of turbines has yet to be determined, but planners are eyeing technology developed by Ocean Renewable Power Co. of Eastport. “The trick at this point is to make sure we look at the impact on the ecology here,” Arnold said.

Arnold envisions an international ocean energy hub based in Lincoln County, with Wiscasset playing a major role in addressing worldwide global warming. He sees, as a fourth and more amorphous project, a research and educational center devoted to ocean energy. An existing partnership with the University of Maine and Maine Maritime Academy to conduct research for the tidal project could give rise to the development of a skilled ocean energy work force in Maine, he said. Aquabank could attract ecotourists, offering bus tours 2.5 miles below the surface showcasing the system’s mechanics.

Town Manager Arthur Faucher is equally eager to contemplate the fruits of the academic alliance in Wiscasset. Students could intern at Chewonki and buy goods in town during their stay, initiating a ripple effect of economic opportunities all over the state, he said. “There’s a little corner in Maine here that has the infrastructure for new energy,” Faucher said. “And that little corner is called Wiscasset Maine.” Riverbank’s project could anchor one of the largest tourist destinations in Maine, said Scott Houldin, a principal in Point East, a subsidiary of National RE/sources, the Connecticut-based real estate development firm that owns the 400-acre Maine Yankee property and Mason Station. “We think it’s a great reuse of the land for Wiscasset,” he said.

Houdlin echoed comments by others involved with the projects that Wiscasset’s history as an energy town, beyond the power lines and railroad tracks, could be revived. “I don’t think you’ll find a community in Maine more knowledgeable about energy than Wiscasset,” he said. Town manager Faucher agreed, comparing energy in Wiscasset to shipbuilding in Bath or papermaking in Millinocket. “People still talk about Maine Yankee,” he said. “It’s interesting how these engineers are still floating around. You can talk energy with them, they understand it.” Local reaction has been positive, but people are reserving judgment until the projects move beyond the concept phase, he said. In the end, all, one or none of the projects could ultimately be developed.

The “No trespassing” signs at Maine Yankee may remain, but many hope to put out the welcome mat at the other sign in town, the one visitors pass before cresting the hill toward downtown and the famous Red’s Eats takeout stand. It reads: “Wiscasset: Prettiest Village in Maine.” The jobs and taxes offered by another energy development in town would undoubtedly be welcome, Shadis said, but he questions whether the town’s history as an energy hub will influence the projects one way or another. “It’s really hard to plumb the psyche of Wiscasset,” he said. “I’ve lived here a long time, 40 years, and I’ve not been able to put a single handle on what the attitude of the town of Wiscasset might be.”

Jackie Farwell, Mainebiz staff reporter, can be reached at jfarwell@mainebiz.biz.

Read Part 1, "Gale force"

Read Part 3, "Grid lock"

Comments