One Wednesday in 2009, Mark Patterson received a letter from his bank that his company had transferred a payment to a bad account. When he met with his CFO the following day, he was told the problem was much bigger: hundreds of thousands of dollars had been transferred out of the company’s checking account, transfers […]

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Mainebiz and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Maine business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the Mainebiz Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

[bypass-paywall-buynow-link link_text="Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article"].

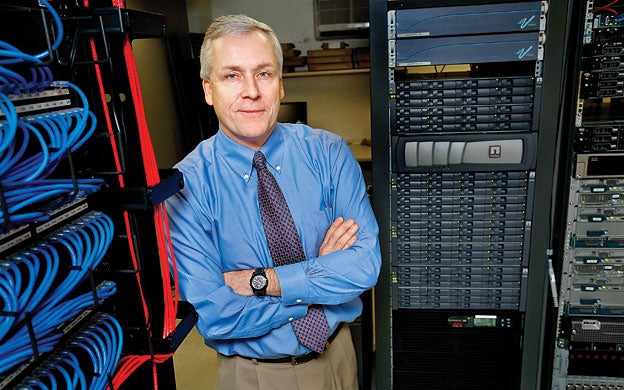

One Wednesday in 2009, Mark Patterson received a letter from his bank that his company had transferred a payment to a bad account. When he met with his CFO the following day, he was told the problem was much bigger: hundreds of thousands of dollars had been transferred out of the company's checking account, transfers he knew couldn't be correct.

“My heart started racing,” he says, the incident that happened four years earlier still fresh in his mind. Over seven days in May 2009, the company's bank authorized six apparently fraudulent withdrawals from the checking account of his company, Patco Construction Co. Inc., a small property development and contractor business in Sanford. The perpetrators took a total of $588,851.26 from Patco's account at Ocean Bank.

“We had put our money in the bank to keep it safe,” says Patterson, who co-owns Patco.

As it turned out, Patco's computers had been hacked. And unlike consumer accounts, for which the account holder is responsible for only about $50 of the stolen money, commercial accounts have no such protection. While the bank blocked or recovered about $243,000, Patco was still missing $345,000 that the bank refused to reimburse. Patco sued Ocean Bank's parent, People's United Bank, and while the U.S. District Court in Maine found for the bank, the U.S. Court of Appeals in Boston reversed that decision. Not only was the case the first such cybercrime to reach such a high court, it ultimately would turn the tables on banks' potential liability. The Patco case also has served as a wake-up call to both banks and small businesses that weren't focusing or investing enough in security.

The legal case came at a time when federal regulators were acting on the increasing incidence of online crimes. The most notable perhaps was in 2005, when Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council agencies, responding to the rise of online banking fraud, issued guidance titled, “Authentication in an Internet Banking Environment.” The guidance said authentication methods that depend on more than one factor, such as a password, an ATM card and/or a biometric characteristic such as a fingerprint, are more difficult to compromise. That 2005 guidance was updated in 2011 with a focus on layered security and customer authentication. The new FFIEC guidance cited “the increasingly hostile online environment.”

Indeed, the Aite Group, a Boston-based advisory group, estimates that corporate account takeover, or cyber fraud, will result in $523 million in losses globally this year alone, a number that it projects will reach $794 million in 2016. Aite also estimates that 87 million new, unique strains of malware will be released per year by the end of 2015. The news is not entirely bleak, the group notes in a report, as the industry has developed a number of approaches to protecting itself.

“Between the Patco attack in 2009 and the final ruling in 2012, there were significant enhancements made in security-related technologies. These enhancements, coupled with a greater understanding by all parties of the threat environment, have resulted in a more secure cash-management system,” says Sari Stern Greene, founder of Sage Data Security LLC in Portland, who served as an expert witness in the Patco case. She adds that Maine community banks, in particular, have always been very focused on the safety and security of their customer funds and information.

Reasonable protection

Where Patco finally won the case was on the concept of the “commercial reasonableness” of Ocean Bank's security procedures, explains the company's lawyer, Dan Mitchell, a shareholder in Bernstein Shur in Portland. That standard falls under Article 4A of the Uniform Commercial Code governing funds transfer. Mitchell explains that in the case of an unauthorized transfer of funds, the initial risk of loss is on the bank, but the bank can shift the risk back to the commercial customer if certain conditions are met. Those conditions are a mutual agreement on security procedures, a recognition that those procedures need to be commercially reasonable and the bank's showing that it followed the procedures in good faith even if the customer didn't authorize the transaction.

What happened in the Patco case, according to court records, is that the perpetrators correctly supplied Patco's customized answers to security questions. The bank's security system flagged each transaction as unusually “high risk,” as they were inconsistent with the timing, value and geographic location of Patco's regular payment orders. However, the bank's security system did not notify its commercial customer, and let the payments go through.

“Ocean Bank in part didn't follow the procedures. We won on commercial reasonableness,” says Mitchell. “The bank didn't pay attention to the red flags raised by its own system.”

The perpetrators were able to siphon off the funds by infecting Patco's computer system with Zeus Trojan malware. Mitchell says that keylogging malware can tell if a customer is logged into the bank and perpetrators can see the password, user ID and challenge questions each time the bank's computer was accessed online.

The frequency of the challenge questions also proved to be a problem, he says. Ocean Bank had set its system so a security question was asked every time Patco transferred $1 or more, a practice he says was unusual at the time. “The keylogger could get the answer to a question, so the chances of a compromise [with frequent questions] are dramatically increased,” he explains.

Adds Mitchell, “The significance of Patco is it is the first high-level, high-profile case that got to the federal court of appeals, and the bank was found to have unreasonable security procedures.” The appeals court recommended the two parties resolve the matter to save resources. In November 2012 the case was settled when the bank agreed to reimburse the remaining losses, plus interest, to Patco. However, each party paid its own legal expenses, which proved to be high. Insurance typically doesn't cover these kinds of cyber losses, Mitchell says, though policies with riders for cybercrime have emerged recently.

“We had hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal fees,” says Patterson. “So even after we got the $345,000 back, we lost hundreds of thousands. Despite the legal expenses, we decided to go forward with the lawsuit, because we felt we were right. This hurt us, but it didn't put us out of business.”

Reflecting back now, Patterson says the case is a wake-up call for banks to review their security measures. He's done the same at his own company. Patco hired Sage Data Security to do a forensic analysis of its systems and to make security recommendations.

Nowadays, Patterson eschews Automated Clearing House payments, instead preferring to mail out payroll checks. The company also set up a dedicated banking computer. “The Zeus Trojan happened when people were on the Internet,” he says. “The banking computer is in the basement, next to the server. We only turn it on when checking the bank accounts.”

Patco was unusual

Chris Pinkham, president of the Maine Bankers Association, says the Patco case was very unusual. “I don't want to leave the impression that this is going on all over the place,” he says. “The systems are very secure.” When there are security problems, the bank systems are reinvented, he says.

“There's a general awareness now that commercial clients need to receive as much education as possible about fraud,” Pinkham says of the ramifications of the Patco decision. “You don't want to be on the front page of the paper, whether you are a bank or a commercial customer.” Corporate account takeovers rarely find their way into the press, because the parties settle quietly.

Lori Desjardins, a partner at Hudson Cook LLP in Portland, says financial institutions are implementing more layered security, especially when they deal with customers who engage in high-risk transactions where money is transferred out, such as ACH and wire transfers.

“There is an increase in the use of tokens. They've been around for a while and are not foolproof, but more banks are using them,” she says. A token looks like a thumb drive with a screen that flashes a temporary password, which changes frequently. They're used in addition to multiple layers of security.

Desjardins says out-of-band technology, where a customer will initiate a transaction via computer network, for example, and the bank responds on a different band, such as calling a customer or texting, also are gaining in popularity.

Overall, she recommends that banks customize security products for their commercial clients. “Make sure you understand and risk-assess each customer,” she advises. “You and your customer need to understand what the security procedures are and what is available. If the customer declines some security, you need to memorialize that in writing.”