In Arundel, marine trade school tries a new tack to weather pandemic

Courtesy / The Landing School

Richard Downs-Honey, left, president of the Landing School in Arundel, maintained social distancing by driving his pickup truck to the homes of recent graduates and “handing” them letters of congratulations via boat paddle. Tom Williams graduated from the school’s yacht design program.

Courtesy / The Landing School

Richard Downs-Honey, left, president of the Landing School in Arundel, maintained social distancing by driving his pickup truck to the homes of recent graduates and “handing” them letters of congratulations via boat paddle. Tom Williams graduated from the school’s yacht design program.

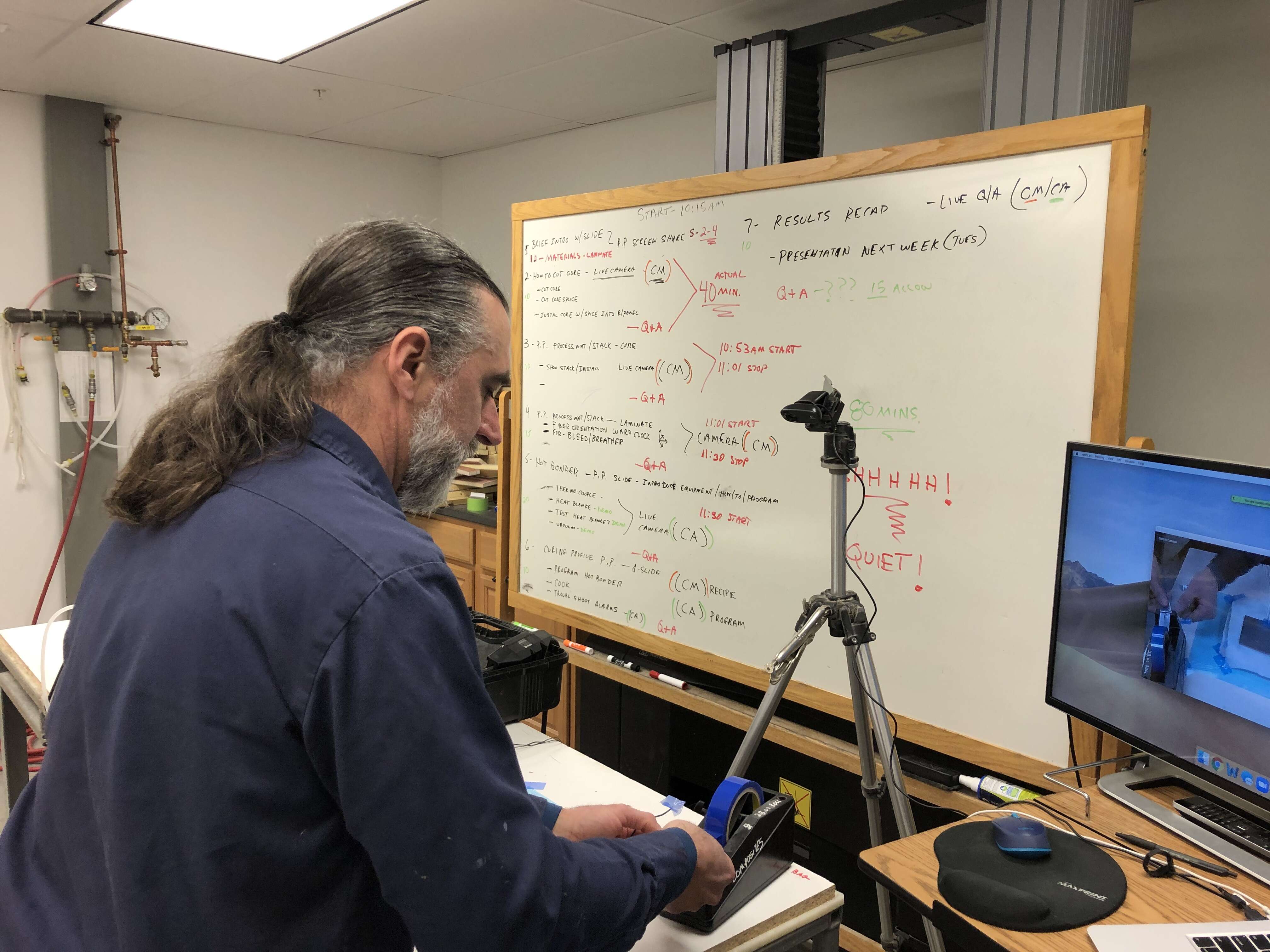

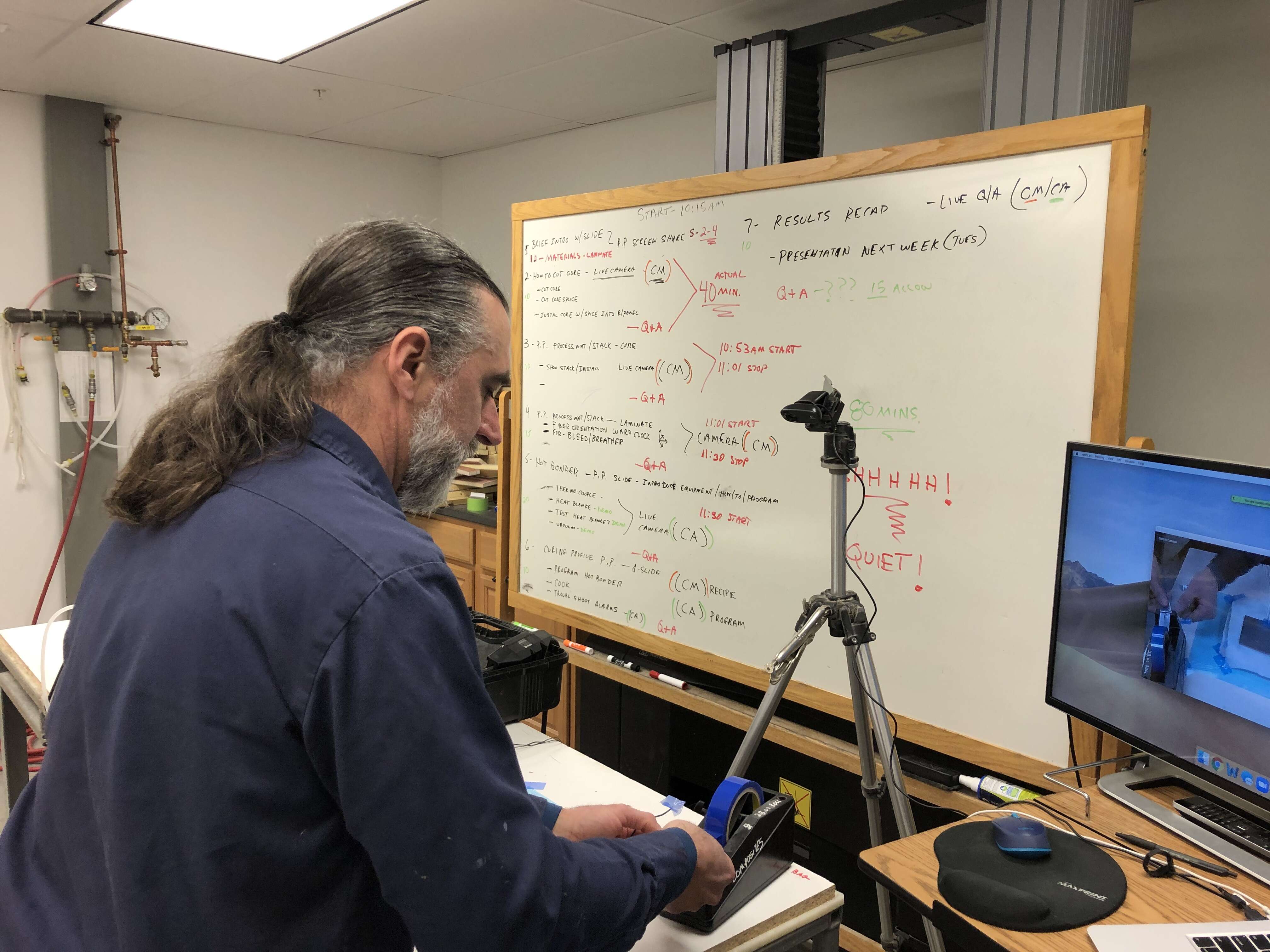

Remote instruction during the pandemic has been a huge shift for teachers around the world. But for the Landing School in Arundel, the trick was how to continue programs where students learn things like how to build boats — through hands-on instruction.

The Landing School is a post-secondary marine trade school for people ranging in age from 18-57. The school has pivoted to continue training its students despite the restrictions associated with COVID-19, and is now pulling together some clever graduation events. They include the school’s president, Richard Downs-Honey, driving around in a pickup truck and extending letters to local members of the graduating class via boat paddle.

On May 15, students with the yacht design program celebrated via virtual graduation. The wooden boat building program will host an onsite, socially distanced “model review” on May 22.

Students have been presenting their final projects and receiving their diplomas over recent weeks despite numerous obstacles presented by the pandemic.

Prior to graduation, students must complete a certain number of classroom and practical hours before submitting a capstone project or senior exhibit, or show evidence of proficiency in their line of study.

For the yacht design students, this translated to a single boat design that showcased their individual abilities.

The wooden boat building program allowed students to work from home on models, with guided instruction, to be evaluated prior to their graduation this coming Friday.

“This year really illustrates the resilience and flexibility of our students and faculty,” Downs-Honey said. “When the COVID-19 crisis hit, most of the students were nearing the end of their classroom work and were launching their hands-on training. We were able to support them through online meetings, shipped materials, and a handful of internships at yards that have been labeled ‘essential business.’”

Downs-Honey told Mainebiz it became apparent the school would have to close right around the time of spring break. A couple of days before the break, the school collected contact information from all of the students and asked faculty to think about what to do for online distance learning.

For a technical school, that was no easy task. While much of the yacht design program is done via computer-aided design, three programs involved hands-on training and construction: wooden boat building, marine systems and composite construction. The wooden boat building students had three yachts under construction. The composites students had fiberglass dinghies underway. In the marine systems program, students were learning how to work on engines and other components of boats belonging to private owners.

But the faculty made the shift, said Downs-Honey.

“It’s amazing what happened in that week,” he said. “All of the faculty came together and by the the end of that week, we were delivering online courses and Zoom meetings, looking at videos and doing demonstrations. Some instructors had cameras set up and did demonstrations.”

The yacht design students transitioned to remote instruction easily. They were all working on their “capstone” or final projects, which involved designing a boat from scratch.

“Instead of them sitting in classes working on a projects, they sat at home working on projects,” Downs-Honey said. “The instructors scheduled specific times to call and talk with the students. All of them competed their requirements on the due date.”

In addition, they got a taste of what it’s like to be a yacht designer in a professional setting.

“Their boss will probably leave to go off to a boat show and expect them to get their work done. So that went well,” he said.

The other end of the spectrum was the wooden-boat building program.

“You’d think that would be the hardest one to deal with,” he said. “The time in the classroom is less than the time on the shop floor. They were at the end of building their boats and had a lot of work to do.”

The students had to abandon those projects. Instead, the lead instructor found a scale model of a sailboat called a Dark Harbor 17. The school shipped the materials and tools needed to build the models to the students’ homes.

“Every day, the instructors would talk with them as a group and individually,” he said.

One would think building a model size boat is not exactly the same as building a real boat, he said. But the exercise required close attention to accuracy that can be more difficult to achieve at a small scale.

“Some students put in 12-hour days working on these,” he said.

The real boats that were under construction are still sitting in the school’s shop. Some students might come in the summer to work on them, he added.

Students in the composites program were also in the middle of working on their capstone projects. They had learned their skills building dinghies and were given free rein to make projects of their choosing. Ideas in the works included a stand-up paddleboard and a cooler that doubled as a boombox, with LED lights and Bluetooth capability.

“All of the guys had their own ideas what they wanted to build,” he said. “But we can’t send buckets of resin to their homes and ask them to work in their kitchens.”

Instead, some students found work on projects at nearby boatyards that allowed them to get enough hands-on hours to fulfill their requirements. But in general, the faculty was stymied. The marine systems program had similar challenges, although some students similarly found work at nearby yards.

As a result, the school was able to get permission from its accreditation body to extend those students’ graduation date.

“Some of the marine systems guys who found work at Portland Yacht Services and other places managed to build up the experience they needed and can graduate now,” he said. “Some need more hours and will come back to complete their projects.”

Looking ahead, Downs-Honey expects the graduates’ employment prospects are as good as any other year, he said. The school’s employment rate approaches 100% most years.

“The students are leaving as qualified as any others,” he said.

Still, he added, the graduates are walking into a job market with massive shutdowns and unemployment.

“They’ll be up against other people who are unemployed, so it will be a difficult thing to measure,” Downs-Honey said. “But I think the opportunities for short-term employment are pretty good. The boat yards and builders have been closed for a period of time and may have lost workers for whatever reason. Even if they manage to get all of their workers back, they’ve got a backlog of work that they’ve got to get done. At this stage, the general feeling is that they’re primed to take advantage of opportunities as businesses reopen.”

As for the next school year, the school is getting a good amount of interest from prospective students. Given the uncertainty of the times, the school is looking at various combinations of online and on-site instruction, with health and safety protocols in mind as well as the possibility of future shutdowns.

“The next year is about planning for contingencies,” he said. “But through this exercise, or run-though, we figured out what we can do, what would be difficult, what things work, and what things we have to improve. The processes and procedures weren’t in place, but we jumped into it very quickly and came up with innovative solutions.”

0 Comments