In the zone | Two companies open their warehouses to activate Auburn's foreign trade zone

After five years of inactivity, the foreign trade zone in Auburn seems to be finally stirring into life, buoying city officials’ hopes that more trade business will follow.

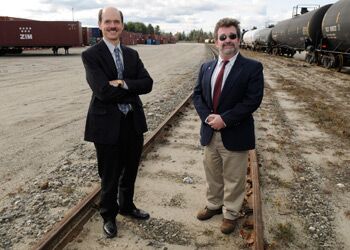

Two local companies, Safe Handling Inc. and NEPW Logistics Inc., this October became the city’s first participants in its five-year-old foreign trade zone. The companies plan to lease warehouse space to other businesses that want to benefit from the lower tariffs associated with foreign trade zones.

A foreign trade zone, or FTZ, is like a regulatory no-man’s land for companies doing international business. The companies participating within the zone are charged lower or no duties on goods they bring into the country and send out domestically or internationally.

But while it sounds good, few companies in Maine in the past 15 or so years have taken advantage of FTZs. And it’s not easy to set one up. Economic development specialists in Lewiston and Auburn spent a couple of years and thousands of dollars to create their 760-acre zone centered on the Auburn airport before it was approved by the U.S. Department of Customs in 2004.

Since then, they’ve marketed the zone consistently — yet had no takers until last month. “The simple reason in Maine is that a lot of companies are unfamiliar with the concept of a foreign trade zone,” Paul Badeau, Lewiston-Auburn Economic Growth Council’s marketing director, says. “Because no one uses them, you may scratch your head and say, ‘How come?’ First of all, you have to conduct enough international trade to make sense to use it.”

Neither of the two new FTZ companies in Auburn will use the zone for much of their own international trade, though. Rather, Safe Handling, a bulk product transportation and toll processing company in Auburn, and South Paris-based NEPW, an operator of warehouses mostly for Maine’s pulp and paper industry, are both offering the FTZ as a service to other importers. Both companies have dedicated more than 100,000 square feet of storage space for this purpose. “This will be something we offer the customers as a whole range of services,” says Ford Reiche, president of Safe Handling, which is in the process of being acquired by Salt Lake City, Utah-based Savage Services Corp.

The Lewiston-Auburn Economic Growth Council will help the two companies find clients, such as smaller companies that could lease their warehouses and get the FTZ advantages without having to apply to be an FTZ user, according to George Dycio, an economic development specialist with the council. The growth council found its FTZ pioneers in the nick of time: They needed a business to activate the zone by Oct. 1 or risk losing Auburn’s trade zone designation. In return for Safe Handling and NEPW’s commitment, the council waived each of their $2,000 activation fees until they secure a user, and also absorbed the attorney fees for the set-up.

Even though the FTZ has involved a lot of work for little immediate benefit, city officials say the zone is part of a larger, far-reaching vision for the cities of Lewiston and Auburn. “It was a lot of work to get the zone activated, time and effort and money, but we see it as part of the whole logistics/transportation hub here,” Dycio says.

Badeau agrees. “The benefits to Lewiston-Auburn are manifold,” he says.

LA’s transportation vision

The community of Lewiston-Auburn has in the past decade been building to be a vital transportation and logistics hub. The area has an airport, two turnpike exits, an intermodal facility, rail connections, even a U.S. Customs port. Badeau says Lewiston-Auburn might not have gigantic bustling ports, like New York or New Jersey, or their wide highways and multi-track train stations, but it also does not have their traffic snarls. Not just trucks but even shipping vessels get mired in jams at busy ports, Badeau points out.

“We don’t have the congestion that they do,” Badeau says. “Now, if you look at forecasts for truck and even deep-sea port routes, it’s the heart-attack map, you can see how much congestion is anticipated over the next five to 10 years.”

Competitive companies that need to find efficient ways to move their goods could increasingly seek quieter, out-of-the way ports like Auburn’s, he says. Say, for instance, if there is an emergency at another port — an oil spill, an embargo or even a pirate attack — companies will need alternatives. “You can’t tell Wal-Mart you’ll get them their products in two weeks,” Badeau says. “It’s great to have an expeditious way to get product from one place to another.”

Auburn doesn’t have a deep-sea port like Portland, but the FTZ extends all the way to Portland, covering not just the 760-acre parcel carved out for it in Auburn, but all land within a 60-mile radius, or 90-minute drive, from the zone’s borders.

And Badeau makes the case that because Lewiston-Auburn is connected to “the rest of the world” via the St. Lawrence and Atlantic railways, which connect to rail lines running from the deep-sea ports of Halifax and Vancouver, the twin cities could become a critical international junction. “It is via those international trade routes that we’re linked in,” he says. “So this little tiny non-water port can suddenly become a major player because of those connections.”

In this grand plan, the FTZ is just one more amenity to strengthen Lewiston-Auburn. The zone works by reducing the tariffs on goods coming into the country if a company assembles these parts into a finished product — a car engine or ballpoint pen, for instance — and sends out the new product domestically. The only tariff the company has to pay is for the new assembled product, which is less than the cumulative tariffs for its individual parts. And no tariff is paid if the product is shipped overseas. It’s as if it never came onto U.S. land.

FTZs also allow companies to defer Customs payments to the U.S. government while products sit in a warehouse. And if a product is broken or obsolete, a company doesn’t have to pay anything, Badeau says.

Scott Taylor is a lawyer with the firm Miller and Co. P.C. in Kansas City, Mo., which specializes in customs and trade, and has helped the growth council implement the FTZ. He calls the zone “another tool in the toolbox for companies looking to relocate operations. It’s another reason to relocate to a community.”

FTZs in action

Foreign trade zones were set up in the 1930s to facilitate trade and increase global competitiveness. At the moment, the United States has about 250 active general purpose FTZs and 450 sub-zones (or smaller specific zones located at a business). Maine has three active zones — in Bangor, Madawaska and Auburn — and one inactive zone in Waterville. All of them are seeing little activity.

This could be in part because joining an FTZ requires upfront costs and a warehouse, and companies have to be doing a certain volume of international trade for them to see significant savings. “It has to be someone who imports a lot of material,” Dycio says, like L.L.Bean or Bath Iron Works. At the time the city was preparing its case for FTZ status, several local companies, including L.L.Bean, Tambrands and Formed Fiber Technologies, testified before federal officials about the prospective benefits an FTZ could bring to their companies. But once the designation was conferred and the companies crunched the numbers, the motivation wasn’t there, says Badeau.

Even big companies are slow to warm to the FTZ. BIW President Jeffrey Geiger says the shipyard has no current work that would push the company to use the FTZ.

Joining an FTZ is only sensible if there’s enough savings in tariffs to offset costs. FTZs are not free to participate in — companies pay a $3,200 to $6,500 application fee, and an annual fee of 15 cents per activated square foot up to 99,999 square feet, and 10 cents for footage over 100,000 square feet up to $20,000 annually.

But now that Safe Handling and NEPW have activated the zone, officials say more activity could spring up. It is not uncommon for FTZs to take some time to warm up, Taylor explains. “The problem communities face is you need to have at least an initial warehouse that’s open for business and activated in order to attract some of this activity,” he says. “There hasn’t been an activated warehouse until now.”

Badeau says Safe Handling, for instance, will now be able “to tell their clients we can do everything from soup to nuts: We can transport your product, store it in a warehouse, mix slurry for paper companies. It’s one more service they can add.”

President Ford Reiche says he’s not sure yet what type of revenue he’ll see from the deal. “It’s one of those things where you don’t know what the future holds,” Reiche says.

NEPW President Drew Gilman says his company inherited the FTZ after recently acquiring the company LynxUS, which had started the application process a year earlier. Gilman says none of his current customers could make use of the FTZ in the former LynxUS warehouse in Auburn, but that he plans to market it to new customers.

While it’s unclear at this point what type of business the new activation will stir, the FTZ zone does ensure that companies in Lewiston-Auburn can find a local, cost-efficient way of moving goods in and out of the country. And that’s a selling point.

“We can market Lewiston-Auburn as a great place to live and do business and we can also say we have an active foreign trade zone,” Dycio says. “So if we have an importer looking for a distribution/warehouse center, they’ll find it here.”

Rebecca Goldfine, a writer based in Dresden, can be reached at editorial@mainebiz.biz.

Comments