Processing Your Payment

Please do not leave this page until complete. This can take a few moments.

- News

-

Editions

View Digital Editions

Biweekly Issues

- December 1, 2025

- Nov. 17, 2025

- November 03, 2025

- October 20, 2025

- October 6, 2025

- September 22, 2025

- + More

Special Editions

- Lists

- Viewpoints

-

Our Events

Event Info

Award Honorees

- Calendar

- Biz Marketplace

Paying a premium | Maine insurers try to stay one step ahead of rate hikes related to weather and climate change

Photo/David A. Rodgers

Chris Condon, president-elect of the Maine Insurance Agents Association and the CEO of United Insurance

Photo/David A. Rodgers

Chris Condon, president-elect of the Maine Insurance Agents Association and the CEO of United Insurance

Photo/Whit Richardson

MMG Senior Vice President Matt McHatten says recent storms have reduced the insurance company's profit margin

Photo/Whit Richardson

MMG Senior Vice President Matt McHatten says recent storms have reduced the insurance company's profit margin

Rising sea levels, melting glaciers, ferocious weather patterns — climate change at the rate it may be occurring is unprecedented. It’s a phenomenon that requires scientists to evaluate and reevaluate its likely impact: Where will temperatures rise and by how much? What will happen to ocean tides? When, where and how often will catastrophic storms or drought occur? Climate change analysis is a confusing and speculative science, and it therefore presents a unique problem for the insurance industry, which is lately realizing its risk assessment models based only past events may ignore critical threats in a picture still developing.

Since 2004’s eight rapid-fire hurricanes were followed by 2005’s record-breaking damages from hurricanes so destructive their names — Katrina, Rita, Wilma — continue to reverberate in the collective American consciousness, property insurers and their trade organizations have paid more attention to climate change data, though the application of reams of dense and occasionally contradictory data varies by company. The volatility inherent in climate change rankles the industry, says David Unnewehr, assistant vice president of policy research at the American Insurance Association, a property and casualty insurance trade organization based in Washington, D.C. “The top-notch science experts that are serving as consultants to the insurance industry — AIR [Worldwide Corp.] in Boston, RMS at Stanford [University in Palo Alto, Calif.] — they are grappling with that issue right now. They’re trying to look at it and see if there’s a way of capturing some of these predictions and building them into the models.”

Maine insurers have noted the extreme weather patterns, though from a relatively sheltered perch compared with insurers in more battered states along the southern Atlantic Coast.

“The weather patterns of recent years have changed how the insurance companies are looking at their data,” explains Chris Condon, president-elect of the Maine Insurance Agents Association and CEO of United Insurance, a Falmouth-based network of 12 insurance agencies in Maine. Condon says Maine insurers first started paying closer attention to climate change predictions in 2004, when, in one of the most active hurricane seasons in decades, eight hurricanes hit the U.S. coast, causing an estimated $25 billion in total damages. And Mother Nature made sure climate change stayed on the insurance industry’s radar — the following year, Hurricane Katrina helped shatter the previous damages record set in 2001 by nearly two-to-one by contributing to 2005 total hurricane season insurance losses of $62 billion, according to insurancenews.net. Recently, 2008 proved to be a rough year, causing $11 billion in catastrophic insurance losses around the country.

Condon says Maine insurers have since modified their risk models to consider whether a property is vulnerable to a catastrophic disaster over the next 500 years, rather than the previous industry standard of 100 years. Though Maine’s catastrophic weather events remain relatively infrequent (unlike in Florida and Texas, for example, which have been so battered by hurricane damage legislators are scrambling to keep state-run coastal property insurance programs solvent), some Maine property insurers have modified premium prices and plan details along the coast, which is considered more vulnerable than inland areas to freak weather patterns like those associated with global warming, as well as to sea level rise.

Here in the Pine Tree State, insurers are more worried about ice storms than hurricanes. Here, too, coastal properties are the concern. In the ice storm of 1998, the sandy southern coastal counties of York and Cumberland, more vulnerable than the rocky northern coastline, were hit the hardest — nearly 3,200 of the 3,901 total insurance claims from that storm came from those two counties, accounting for $8.8 million of the $11.1 million in total ice storm-related losses to insurers in the state, according to the Maine Emergency Management Agency.

“What we’re seeing locally is insurance companies have changed their view of what premiums they should develop for coastal properties,” explains Condon. For example, Condon points to one of MIAA’s member companies that has since 2007 raised its rates 70% on coastal properties in York County, the county most damaged in the 1998 ice storm. Another company has changed its definition of coastal property, for which it charges higher rates, from within 1,000 feet from the coast to within 5,280 feet, or one mile. Another has added wind deductions, also known as hurricane insurance, that typically force a client to pay an average of 6% to 14% of the property value before the insurer will pay for damage from winds above 74 miles per hour. Phone calls to several York and Cumberland County insurers went unreturned, and Condon would not name the companies he spoke of. “It’s fair to say that every insurance company that I’m aware of in coastal Maine has modified their coastal insurance.”

Reinsurance prompts changes

Just as climate change affects the environment in an intricately interconnected way — in which melting in the Arctic, for example, could affect lobstering off the Maine coast — so do weather catastrophes far from Maine influence the cost of premiums here. The reason is the reinsurance market — the multi-billion dollar industry that provides insurance to the insurers.

To make sure they can cover catastrophic losses, property insurance companies insure their own policies with a handful of global reinsurance giants like Munich Re, Swiss Re and the reinsurance arm of Berkshire Hathaway. That way, if the insurer’s risk projections are wrong and one year more clients cash in their policies than expected, the insurer will remain afloat because reinsurance will pick up the balance. Reinsurance rates can directly affect the cost of the policies the company offers, because the more the insurer has to pay to cover all of the policies it’s written, the more cash cushion it may need to generate from higher premiums. Reinsurers have lately increased their premium costs because of recent catastrophic losses and the global financial crisis’ impact on the reinsurers’ access to capital. And so, even though Maine’s last major catastrophic loss for insurers was the ice storm that occurred over a decade ago, reinsurance premiums for the state and northeast region this year alone increased by about 8%, according to Investment News. Still, that hike is better than the national average — 15% year-over-year — and it’s a fraction of the Gulf Coast year-over-year differential of 30% to 40%.

Maine Mutual Group Insurance, or MMG, is the only property casualty insurance company covering Maine that also has its executive offices in state in Presque Isle. The company, which was founded in 1897 and last year generated $114 million in revenue from about 100,000 unique policyholders, in 2006 expanded into Pennsylvania. MMG has since the early 1980s operated in New Hampshire and Vermont as well as in Maine, and three years ago entered the Pennsylvania market because the area is less prone to extreme weather than other parts of the country.

“If we are able to diversify our company from exposure to weather, it gives us an ability to be more stable in the future,” says MMG Senior Vice President Matt McHatten. And this stability is critical for MMG. McHatten says that in 2007, the company’s historically healthy profit margin narrowed because of severe ice and snow storms that year, and last year damage from similar unforeseen weather whittled that profit margin away to zero. And then, McHatten says, there’s the rising cost of reinsurance.

Because of reinsurance rates, MMG recently raised premiums in storm hotspots York and Cumberland counties between 7% and 10% on average, with some coastal properties seeing even sharper increases. (McHatten stresses rates vary above or below the average based on the type and location of the property.) McHatten says MMG follows the latest climate change reports from the major reinsurers, but the data it uses for risk assessment continues to be generated from past weather events, as has long been the industry standard.

“As a company that is impacted significantly by the weather, we are very interested in what’s going on with climate change,” says McHatten, “but in the immediate, it’s much more about looking at weather patterns and making sure that we’re prepared for what hits.”

Sara Donnelly, a contributing writer, can be reached at editorial@mainebiz.biz.

Maine readies for change

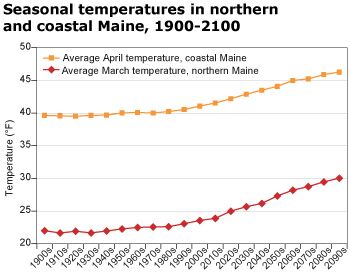

President Obama has declared that addressing climate change is one of his administration's priorities, and here in Maine, the Legislature this year convened a stakeholder group of business, nongovernmental and state agency representatives to begin to craft a public policy strategy to mitigate and adapt to climate change. According to a February 2009 study by the University of Maine and the UMaine-based Climate Change Institute, "Maine's Climate Future," Maine could warm by an average of 3 to 12 degrees in winter and 3 to 10 degrees in summer, depending on the region of the state, by the end of the current century. Climate change-related warming and other effects, like sea level rise and ocean temperature changes, would affect, in some cases positively, every major natural resources industry in the state.

Specifically, the report's executive summary says that for the 21st century, Maine will likely experience warmer and wetter seasons year-round. The implications are multiple: longer mud seasons and shorter hard freezes that will impede traditional forest harvesting; warmer oceans that prompt more and fiercer hurricanes and create a less welcoming habitat for cod; fewer spruce trees, loons, chickadees, lynx, halibut and moose, but more oak trees, bobcats, flounder and deer.

In the face of climate change data, violent hurricanes in the Gulf Coast and ice storms, potato blight and unexpected rainy seasons in Maine that, accurately or not, appear to some casual observers as evidence of a changing climate, Maine, like other states around the nation, is feeling constituent pressure to prepare for a changing world. In May, the Maine Department of Environmental Protection convened the climate change stakeholder group to study the climate change report, whose authors stress that Maine's diversity of climates within close proximity to each other, and its economic reliance on natural resources-based industries, makes assessing the impact of climate change a priority.

The panel must present its own report to the Legislature this February suggesting broad ways to mitigate climate change-related damage to the state's natural resources sectors, human health, infrastructure and water supplies.

Augusta lawyer Charlie Soltan, spokesperson for the Maine Association of Insurance Companies, represents the insurance industry on the climate change stakeholder panel. For Soltan and others in Maine's insurance industry, coastal Maine's vulnerability to hurricanes, sea level rise and ice storms means insurers not only need to reevaluate risk, they also need to play a key role in crafting public policy to mitigate that risk. And some in insurance say the industry's policy impact should be loftier than simply influencing rates - some insurers are offering premium discounts for green practices like owning a hybrid car, and it was the insurance industry, after all, that convinced policymakers decades ago to create emergency fire departments.

"We hope to bring our perspective to the table," says Soltan of his participation in the stakeholder panel, "because most of the groups wouldn't be aware of how climate change affects the industry."

Sara Donnelly

Risky business

Federal changes to the flood risk map of Portland Harbor made headlines recently as a potential barrier to development on the waterfront. But contrary to how it might appear, the Federal Emergency Management Agency says the changes don't have anything to do with the brouhaha surrounding climate change.

Fortified with new satellite and mapping technologies and mandated by Congress, FEMA is assessing and identifying flood risk in high population areas across the country. It started mapping Cumberland County in 2003, eventually leading to its proposal earlier this month that Portland Harbor be reclassified to prohibit new development and restrict renovations on pile-supported piers.

That news elicited a strong reaction from city officials and local business owners, who met with FEMA officials last week challenging the federal agency's proposal. The agency has agreed to review its analysis and another meeting is planned for early September.

"We made the point that we spent a lot of money building to code and addressing the floodplain issue," says Charlie Poole, whose family has managed the Union Wharf for more than 200 years and where today businesses service oil tankers and other vessels. "The two buildings we built within the last 25 years all had to be raised to two feet above the 100-year flood mark and one foot above the 500-year mark."

Because Union Wharf is built on solid fill surrounded by an apron of piles, Poole doesn't believe it would be affected by the reclassification. But he empathizes with the other pier owners and worries that any enhanced regulation will derail renovations and developments along Portland's working waterfront.

That includes the availability of flood insurance, which FEMA provides, on bank loans. If the agency prohibits development under a reclassification, it would not provide the insurance, making the likelihood of getting a loan slim.

"It's a Catch 22," Poole says.

Dennis Pinkham, a spokesman for FEMA's Boston office, said the mapping was done independent of any concerns about climate change or recent weather-related events. Nor was there any kind of financial impact study attached to the project, since that wasn't the directive from Congress.

"We were charged with identifying and updating flood risk and communicating that risk to the public so that effective strategies can be developed to manage the risk," he said via email.

Carol Coultas

Mainebiz web partners

The Giving Guide

The Giving Guide helps nonprofits have the opportunity to showcase and differentiate their organizations so that businesses better understand how they can contribute to a nonprofit’s mission and work.

Learn More

Work for ME

Work for ME is a workforce development tool to help Maine’s employers target Maine’s emerging workforce. Work for ME highlights each industry, its impact on Maine’s economy, the jobs available to entry-level workers, the training and education needed to get a career started.

Learn More

Groundbreaking Maine

Whether you’re a developer, financer, architect, or industry enthusiast, Groundbreaking Maine is crafted to be your go-to source for valuable insights in Maine’s real estate and construction community.

Learn more-

The Giving Guide

The Giving Guide helps nonprofits have the opportunity to showcase and differentiate their organizations so that businesses better understand how they can contribute to a nonprofit’s mission and work.

-

Work for ME

Work for ME is a workforce development tool to help Maine’s employers target Maine’s emerging workforce. Work for ME highlights each industry, its impact on Maine’s economy, the jobs available to entry-level workers, the training and education needed to get a career started.

-

Groundbreaking Maine

Whether you’re a developer, financer, architect, or industry enthusiast, Groundbreaking Maine is crafted to be your go-to source for valuable insights in Maine’s real estate and construction community.

ABOUT

NEW ENGLAND BUSINESS MEDIA SITES

No articles left

Get access now

In order to use this feature, we need some information from you. You can also login or register for a free account.

By clicking submit you are agreeing to our cookie usage and Privacy Policy

Already have an account? Login

Already have an account? Login

Want to create an account? Register

Get access now

In order to use this feature, we need some information from you. You can also login or register for a free account.

By clicking submit you are agreeing to our cookie usage and Privacy Policy

Already have an account? Login

Already have an account? Login

Want to create an account? Register

Comments