Processing Your Payment

Please do not leave this page until complete. This can take a few moments.

- News

-

Editions

View Digital Editions

Biweekly Issues

- October 20, 2025

- October 6, 2025

- September 22, 2025

- September 8, 2025

- August 25, 2025

- August 11, 2025

- + More

Special Editions

- Lists

- Viewpoints

- Our Events

- Calendar

- Biz Marketplace

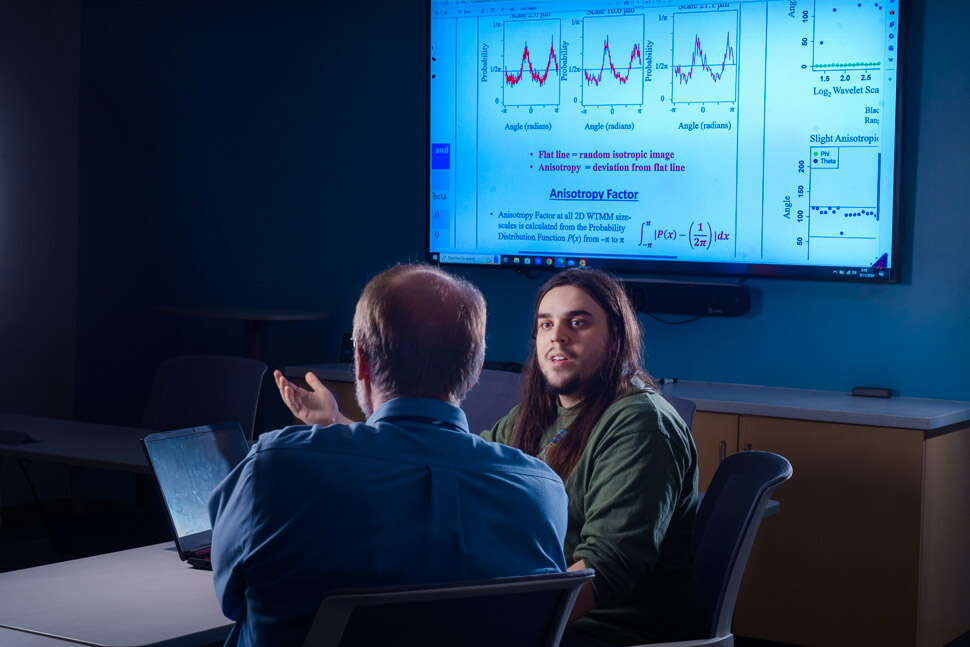

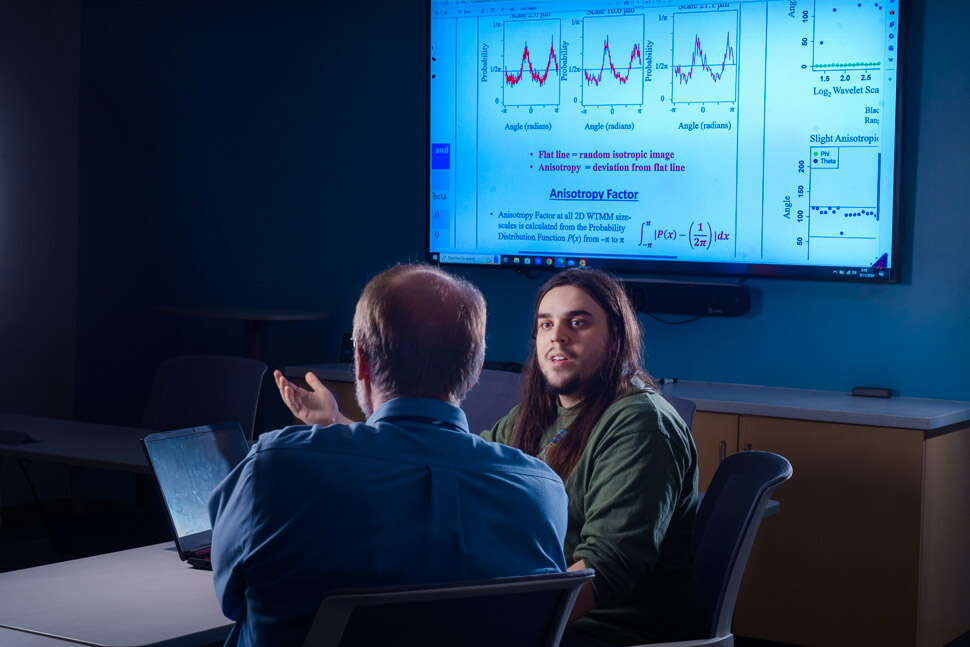

The teacher: How an Old Town teacher helped spark a Ph.D. student’s intellectual drive

Photo / Fred Field

University of Maine Ph.D. candidate Josh Hamilton, foreground, credits his high school teacher, Dr. Rad Mayfield, with pushing him toward higher educational goals.

Photo / Fred Field

University of Maine Ph.D. candidate Josh Hamilton, foreground, credits his high school teacher, Dr. Rad Mayfield, with pushing him toward higher educational goals.

From the start, Josh Hamilton was always a smart student. But he was also bored, coasting through classes, simply doing what he needed to get by.

That changed when his 10th grade biology teacher pulled him aside at Old Town High School and bluntly asked him why he wasn’t taking Advanced Placement biology. Recognizing that Hamilton was a critical thinker with a lot of curiosity, the teacher in his own way challenged the 10th grader to challenge himself.

That impetus had an impact. As a junior and senior in high school, Hamilton took eight AP classes, giving him 30 college credits by the time entered the University of Maine in Orono after high school. He went on to earn a bachelor’s degree, graduating with a 3.89 GPA, and then a masters’ degree. Today, he’s earning a Ph.D. in biomedical engineering, researching early diagnostics of cancer.

The roots of a pursuit

When he was first asked by his 10th grade teacher, Rad Mayfield, why he wasn’t pushing himself more in school, his first reaction was “Why bother?” But then a switch flipped in his brain, changing his outlook and his pathway forward.

“He was the first teacher who said, ‘Just because you’re smart and it’s easy doesn’t mean you just coast by. You need to challenge yourself just like other students are challenging themselves at their levels,’” says Hamilton, who’s now 25. “I needed to challenge myself at my level, but I wasn’t. I’d never had a teacher take me out and have that one-on-one conversation.”

Mayfield says he has always made a point of encouraging students to push themselves. He taught for 26 years, including 12 at Old Town High School, before becoming the principal at Central High School in Corinth two years ago.

“What I did was try to foster their love for a subject. That’s a key,” Mayfield says. “If a teacher can convince a kid that what they’re studying is worthwhile studying, the kid’s going to excel. But it’s challenging to convince kids of that sometimes.”

The value of a teacher

Most everyone has a story of a memorable high school teacher or two who made a lasting impression, or even changed the trajectory of their future in school and beyond. The value of good teachers is more than just anecdotal, however.

Study after study has shown that good teachers in the classroom have a far bigger impact on student achievement than any other aspect of schooling. Good teachers matter more than class size. More than a school’s schedule. More than technology. More than a revamped curriculum.

Attempting to quantify the impact of top-notch teachers, a research project led by economists at Harvard and Columbia concluded that the best teachers also have a profound impact on the future earnings of their students. A high-performing teacher — one in the 84th percentile — produces an increase of $400,000 on each student’s lifetime earnings, the study says. Multiply that by a career’s worth of classrooms and the numbers are staggering.

‘I just coasted by’

While school was always easy for Hamilton, he says nobody urged him to do more. He grew up in what he describes as a low-income household in Alton, a town of less than 1,000 about 20 miles outside of Bangor.

His mother never attended college, and his father dropped out of college before later returning to earn a degree. Household finances were sometimes tight, he says, and his parents divorced when he was in middle school.

“I got bored pretty early on in elementary school with classwork,” he says. “So I just coasted and did what I needed to get by, because I didn’t need to put in a lot of effort to get by.”

Mayfield saw in Hamilton what he’s seen in many students through the decades. For him, the best way to get students enthusiastic is to be passionate about what he’s teaching and hope it rubs off on students.

“You try to make the classes challenging and engaging and fun,” he says. “One of things that drives kids crazy is when they’re bored in a class. I think they’d much rather feel challenged and have to work hard than walk into a class and not feel like they have to work at it. Then they just get bored with it.”

At Mayfield’s urging, Hamilton stepped it up and has continued to do so. For his doctorate, he is studying what is known as tumor microenvironments, researching breast cancer with scientists at the Maine Health Institute of Research. He is looking at the tissue near the cancer, rather the tumor itself, to help predict if the cancer will remain docile or will expand, and how volatile or aggressive it will be.

He plans to complete his Ph.D. in 2026 and hopes to be part of research team after graduation. After being in school for more than 20 years, he’s looking forward to a change from academics and hopes to work in a corporate setting.

His doctoral advisor, Andre Khalil, says Hamilton always take the extra step — or two or three — to learn as much as about a subject as he can. When he first studied coding, or computer programming, in college, Hamilton made a point of learning as much as he could about it even outside of the classroom, so much so that his coding skills now surpass Khalil's in some areas.

Khalil, who is a professor of chemical and biomedical engineering, says he’s seen numerous students through the years whose success can be traced back to a single teacher in secondary school. And like those students, Khalil himself had a math teacher in seventh or eighth grade in the 1980s who inspired him and steered him toward math.

Conversely, he’s also seen students turned off to certain subjects because of a teacher.

“At some point they have someone teaching them who didn’t have that passion,” he says. “Often it comes down to that one teacher.”

Khalil has also seen many students, like Hamilton, from low-income rural families, who are perhaps first-generation college students, excel in higher education; he calls them “diamonds in the rough.”

Not all work

Hamilton’s success isn’t limited to just academics, and he makes an impression on others with his long dark hair, his infectious smile and laugh, and his willingness to help others. Through his college career, he’s taken on leading roles with student organizations, he plays the drums with his musician friends, and he competes in esports such as Super Smash Bros. Melee, in which he is ranked No. 1 in Maine.

He would advise any student to find a teacher early on who can help steer them in the right direction.

“As a student who’s bored, it’s hard to get out of that mindset; you’re young and you don’t have that self-awareness yet,” he says. “But if you know there’s somebody who’s trying to get you out of that, and even if you’re angsty and don’t like what they’re trying to do, just be open to accepting that sometimes you need discipline in your life.”

Mayfield says there’s nothing more satisfying for a teacher than seeing former students succeed. “I’m proud of Josh and other students like him,” he says. “That’s among the greatest rewards for an educator, to know their former students are doing well because that’s what we want them to do.”

But he’s also had times when his efforts have fallen short. As a first-year teacher in North Carolina, he tried talking to and helping a student who had behavioral issues.

“A year later I got a letter from him saying he had moved to Florida and was in jail,” Mayfield says. “He says he had made some bad mistakes, but wanted me to know he appreciated all I had tried to do. Sometimes you don’t succeed.”

Mainebiz web partners

Related Content

The Giving Guide

The Giving Guide helps nonprofits have the opportunity to showcase and differentiate their organizations so that businesses better understand how they can contribute to a nonprofit’s mission and work.

Learn More

Work for ME

Work for ME is a workforce development tool to help Maine’s employers target Maine’s emerging workforce. Work for ME highlights each industry, its impact on Maine’s economy, the jobs available to entry-level workers, the training and education needed to get a career started.

Learn More

Groundbreaking Maine

Whether you’re a developer, financer, architect, or industry enthusiast, Groundbreaking Maine is crafted to be your go-to source for valuable insights in Maine’s real estate and construction community.

Learn more-

The Giving Guide

The Giving Guide helps nonprofits have the opportunity to showcase and differentiate their organizations so that businesses better understand how they can contribute to a nonprofit’s mission and work.

-

Work for ME

Work for ME is a workforce development tool to help Maine’s employers target Maine’s emerging workforce. Work for ME highlights each industry, its impact on Maine’s economy, the jobs available to entry-level workers, the training and education needed to get a career started.

-

Groundbreaking Maine

Whether you’re a developer, financer, architect, or industry enthusiast, Groundbreaking Maine is crafted to be your go-to source for valuable insights in Maine’s real estate and construction community.

ABOUT

NEW ENGLAND BUSINESS MEDIA SITES

No articles left

Get access now

In order to use this feature, we need some information from you. You can also login or register for a free account.

By clicking submit you are agreeing to our cookie usage and Privacy Policy

Already have an account? Login

Already have an account? Login

Want to create an account? Register

Get access now

In order to use this feature, we need some information from you. You can also login or register for a free account.

By clicking submit you are agreeing to our cookie usage and Privacy Policy

Already have an account? Login

Already have an account? Login

Want to create an account? Register

0 Comments