Processing Your Payment

Please do not leave this page until complete. This can take a few moments.

- News

-

Editions

-

- Lists

-

Viewpoints

-

Our Events

-

Event Info

- Women's Leadership Forum 2025

- On the Road with Mainebiz in Bethel

- Health Care Forum 2025

- On The Road with Mainebiz in Greenville

- On The Road with Mainebiz in Waterville

- Small Business Forum 2025

- Outstanding Women in Business Reception 2025

- On The Road with Mainebiz in Bath

- 60 Ideas in 60 Minutes Portland 2025

- 40 Under 40 Awards Reception 2025

- On The Road with Mainebiz in Lewiston / Auburn

- 60 Ideas in 60 Minutes Bangor 2025

Award Honorees

- 2025 Business Leaders of the Year

- 2024 Women to Watch Honorees

- 2024 Business Leaders of the Year

- 2023 NextUp: 40 Under 40 Honorees

- 2023 Women to Watch Honorees

- 2023 Business Leaders of the Year

- 2022 NextUp: 40 Under 40 Honorees

- 2022 Women to Watch Honorees

- 2022 Business Leaders of the Year

-

-

Calendar

-

Biz Marketplace

- News

- Editions

- Lists

- Viewpoints

-

Our Events

Event Info

- View all Events

- Women's Leadership Forum 2025

- On the Road with Mainebiz in Bethel

- Health Care Forum 2025

- On The Road with Mainebiz in Greenville

- On The Road with Mainebiz in Waterville

- + More

Award Honorees

- 2025 Business Leaders of the Year

- 2024 Women to Watch Honorees

- 2024 Business Leaders of the Year

- 2023 NextUp: 40 Under 40 Honorees

- 2023 Women to Watch Honorees

- 2023 Business Leaders of the Year

- + More

- 2022 NextUp: 40 Under 40 Honorees

- 2022 Women to Watch Honorees

- 2022 Business Leaders of the Year

- Nomination Forms

- Calendar

- Biz Marketplace

Rural areas hold opportunity for law grads facing tough job market

PHOTo / Amber Waterman

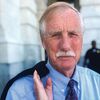

Finding young lawyers to replace those retiring in rural areas is an especially tough challenge, says William Robitzek, president of the Maine Bar Association.

PHOTo / Amber Waterman

Finding young lawyers to replace those retiring in rural areas is an especially tough challenge, says William Robitzek, president of the Maine Bar Association.

News stories about the shortage of dentists and family doctors in rural Maine have appeared regularly over the past two decades. A combination of lower salaries and fewer opportunities for professional advancement have produced apparent chronic shortages in the state's rural counties — and, in response, several programs designed to combat them. There's a state loan forgiveness program for dentists, and new funding for rural health clinics in the Affordable Care Act.

But could an even larger and older profession — law — also be affected by these demographics?

New statistics show that it could. According to Peter Pitegoff, dean of the University of Maine School of Law, some 1,000 of the state's 3,700 practicing attorneys are age 60 or older — a point when at least some are thinking of retirement. And in the five most rural counties, lawyers older than 60 comprise more than half of current practitioners.

While there have been no legislative bills yet to head off a shortfall of legal services, the problem is getting some high-level attention at the law school and at the Maine Bar Association, where the current president, William Robitzek of the Lewiston firm of Berman Simmons, is giving it his personal attention.

Robitzek says that as the nation's oldest state demographically, it only makes sense that Maine would be experiencing professional shortages, and that the shortfalls would be most pronounced in rural areas where population, and often personal income, has been falling. The Maine Department of Labor projected 74 openings for lawyers each year from 2010 to 2020; 54 would be replacement openings and 20 would be new positions.

But finding younger lawyers to replace those retiring in rural areas is an especially tough sell, even for those who graduate from the law school in Portland and want to practice in Maine.

“Portland is a great place to live,” Robitzek says. “It has culture and amenities and that's a real draw for younger people.” For those going to law school there, Maine's largest metro area is often their first choice to launch a career.

But there are some significant economic headwinds. Larger law firms have slowed their hiring rates, shrinking the window for recent grads to land a post with a metro firm.

A study done by the Wall Street Journal and American Bar Association published in October 2012 showed 25.5% of UMaine 2011 law graduates were unemployed nine months after graduation, and of those employed, only 42% were working in jobs that required a law degree. Of the 87 students who graduated from Maine Law in 2012, 19.5% had not found a job as of February 2013, according to the ABA, a rate that is nearly twice the national average of 10.6%.

Other opportunities

Pitegoff says “there is a tremendous need” for legal services in rural areas and that where lawyers are now choosing to practice “is not the right distribution” to serve all parts of the state. The law school has begun inviting judges and attorneys from distant parts of Maine, including Aroostook and Washington counties, to meet with students and talk with them about opportunities to practice outside southern Maine.

It's also taken a more hands-on approach. Last January, Rachel Reeves, senior adviser for career services, took several Class of '13 students on a road trip to rural destinations, including Belfast, Ellsworth, Machias and Bangor. They met judges and attorneys and, for some at least, it was their first experience in those parts of Maine, Reeves says.

Pitegoff adds that the efforts to spotlight rural practices have achieved some visibility, though it's too soon to say how effective they'll be.

The Maine bar has also stepped up efforts. Robitzek has begun trying to match new graduates with older attorneys who might be looking for a successor, or are simply looking to bring new blood into their firms. It's an effort he intends to expand once he steps down as bar president at the end of the year.

The bar also offers other inducements to keep graduates in Maine, including free bar membership, a mentoring program and a litigation institute that focuses on courtroom practices and procedures.

But to meet the demand for their services, freshly minted lawyers might have to adjust their expectations of a first job. Reeves points out that the Maine Department of Labor projects a 7.2% increase in legal sector jobs over the next decade, one of the rosier predictions in a generally bleak employment picture.

Pitegoff says that's because legal training is now in demand for new positions that until recently didn't exist.

“Privacy compliance and data security are huge issues now, not just for large corporations, but for large and even medium-sized nonprofits as well,” he says.

Traditionally, only about half of law school graduates go directly into legal practice; the others are hired by business, government and the nonprofit sector for positions that require legal training.

“Lawyers may not be running these departments, but they're essential to their work,” Pitegoff says.

Whether that translates into creating the kind of staffing of law firms and courts that are required to serve Maine's rural counties is another question, as is whether they will be jobs filled by Maine natives.

“Even some of the out-of-state students end up practicing in rural areas,” says Reeves. “A lot of them don't want to leave once they're here. It is kind of a lovely place.”

Why they stay

Four recent graduates of University of Maine School of Law share why they stayed in Maine, but left Portland.

Steven Nelson, Houlton

For Steven Nelson, it was a fairly natural decision to return to Houlton, where his father has practiced law since 1976 and he became familiar with the profession.

“I attended a few trials and was familiar with legal issues from a young age,” he says.

Although he enjoyed Portland, he had clerked at the Houlton offices of Severson Hand & Nelson, and then decided to join the family firm, which has three other attorneys. Initially, most of his cases were in criminal defense and family court, but he found that some of the firm's specialties, such as real estate and business law, engaged him more.

The ability to work in many different aspects of the law is one of the advantages of a small-town practice, he says. In cities like Boston or Portland, “you almost have to have a specialty to get started. And you may not even get into a courtroom for a long time.”

For Nelson, the close interaction with clients has led him to a broader engagement with the community, where he's already served on several nonprofit and municipal boards.

“That was a big advantage for me,” he says. “It's easier to have an impact on the community right away.”

Victoria Silver, Auburn

Victoria Silver decided to return to Auburn and hang up her solo-practice shingle after graduation in 2012. She keeps expenses down by working out of her home and often takes clients on a sliding-fee scale, based on what they can afford to pay.

She went to law school after working first as a social worker. UMaine School of Law has been rated second in the country by the Princeton Review for its acceptance of older students.

“I didn't graduate until I was 35, but I figure I still have 25 to 30 years to practice,” she says.

Silver's legal work reflects her background in social work. She handles many family cases, including divorce and child custody, and also serves as a guardian ad litem. Civil proceedings are her primary interest, and she most often appears in courtrooms in Paris, Farmington, Rumford and Waterville.

Silver sees the advantages of working in an established firm, and doesn't rule out the idea of working with an older attorney in a kind of succession arrangement.

School loans and leaner economic prospects from the recession make it less likely that a young attorney can purchase a practice, a time-honored way of finding a niche. She says getting hired as an employee at an established firm is probably a more realistic prospect for those who want that path.

Jason Bulay, Farmington

Jason Bulay didn't find relocating to a rural area a challenge, because that's where he wanted to be all along. Originally from Old Town, he worked in Belgrade for five years before attending law school. Even while he was in Portland during the week, he found himself “driving a couple of hours away each weekend” to engage in his passion for the outdoors.

He's now settled in Farmington, where he has a solo practice but plenty of contact with other attorneys; he rents space in the Main Street building owned by the firm of Joyce, David and Hanstein. The western mountains region lets him find time for hiking, skiing and panning for gold.

He most often works as a criminal defense attorney and in family law, but is open to cases that require different skills as well. Proximity to other attorneys has been a plus.

“They've pretty much taken me under their wing,” Bulay says. “They've been very helpful and generous with their time.”

He notes that he's not the only one in his class who's settled in rural Maine. Classmates are now working in Presque Isle and Machias, “and that's about as far as you can go” and still be in Maine, he says.

Taylor Kilgore, Turner

Growing up in Falmouth, Taylor Kilgore liked the sense of a close-knit community, “the way people cared about other people, the small town values.”

And after graduating this year, she's found a similar niche in Turner, where she was invited to join the three-attorney firm of Boothby Perry. She, too, has a background in social work and earned her undergraduate degree from the University of Maine at Augusta through the interactive technology system — “I never saw a classroom the whole time,” she recalls.

Kilgore's hiring came from matchmaking services of the bar association. She was looking for a rural practice, and it was suggested that Boothby Perry might be willing to expand its staff with the right person. Discussions ensued, and “magic happened,” she says.

“I'm fascinated by what walks through the door every day,” she says. In a small town, “everybody knows everybody, and people are willing to talk. They know when they need legal services, and they know who to see.”

Working in a small practice, she's intrigued by the variety of problems that cross her doorstep. She offers a recent case in timber law as an example. “It was something I was completely unfamiliar with. There's always something new to learn,” she says.

Comments