Processing Your Payment

Please do not leave this page until complete. This can take a few moments.

Craftsmen corner niche market in art world

Photo/David A. Rodgers

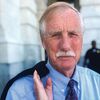

Chris Polson, left, and Joe Calderwood of Twin Brooks Stretchers in Lincolnville just posted their company's strongest year after 15 years in business

Photo/David A. Rodgers

Chris Polson, left, and Joe Calderwood of Twin Brooks Stretchers in Lincolnville just posted their company's strongest year after 15 years in business

In a studio tucked away on 100 wooded acres in Lincolnville, Chris Polson and Joe Calderwood have spent more than 15 years making a name for themselves in the art world. Over that time, they’ve completed thousands of works and garnered the appreciation of well-known painters such as Jamie Wyeth and the late Neil Welliver. Their work hangs in museums and galleries across the country, as close as Portland and New York City and as far away as the Philippines.

And no one ever sees it.

That’s because Polson and Calderwood’s work isn’t the painting itself, but what‘s behind the canvas. The pair are the owners of Twin Brooks Stretchers and make custom aspen wood framing called stretchers that support art canvases. Polson, trained in forest management, and Calderwood, an experienced sawyer, build the stretchers for 1,200 customers, mostly professional artists outside of Maine looking for high-quality support for their work and willing to pay a bit more to get it. And though a top-quality stretcher is vital to properly display and preserve paintings, it remains invisible to members of the general public, who would only know its creator if they took it off the wall, flipped it over and spotted the artist’s signature — a stamp bearing Twin Brooks’ name, address and phone number.

But that relative anonymity doesn’t bother them, says Polson, who sees the company’s work as continuing in the footsteps of stretcher makers before them. “It’s a privilege to be a part of that tradition and improve on it. It strikes me as satisfying,” he says. “It doesn’t bother me that there’s no big sign advertising us with each painting. We’re just pleased to see the customer happy.”

Despite flying under the radar, Polson and Calderwood have been successfully, if slowly, building their business. Last year, they expanded their 2,400-square-foot shop by 800 square feet to add a reception area, office space and a bathroom. And while the recession has left wood products companies in the building industry quaking, Twin Brooks posted its best year ever, with nearly $300,000 in sales. Twin Brooks’ success during turbulent times has even helped boost business at Warren-based A.E. Sampson & Son, a hardwood flooring company that mills Twin Brooks’ wood to precise dimensions. “We’re lucky we’ve developed a business not immediately dependent on the housing industry, because we haven’t been feeling the downturn,” says Polson. “Artists still have to paint to make a living.”

Custom work, adding value

Twin Brooks’ blue, box-like shop sits off a muddy rural road, where, on a cloudy day in mid-March, visitors are greeted by piles of aspen logs waiting to be cut and an energetic black Lab named Oskar. Inside, stacks of cut and milled wood are ready to be turned into stretchers, and rolls of gray Belgian linen that will be cut into canvases lean against the walls. Polson’s own landscape oil paintings hang around the shop, serving as both decoration and product display.

Though it’s a small operation, the company holds a unique spot in an already niche market by being the only stretcher company that takes the wood from log to finished product. A handful of logging companies in Maine supply the aspen, a junk wood by lumber standards that’s used mostly for pulp, but is ideal for art frames because it’s sturdy, lightweight and doesn’t tend to splinter, Polson says. Twin Brooks saws the logs on site, lets them air dry outdoors for about three to six months and dries them for a week in their oil-fired kiln. Then, A.E. Sampson & Son picks up the wood and trucks it back to its office in Warren, where the wood is given the slight beveled edge needed to properly support the canvas.

Back at the shop, Polson and Calderwood turn those milled pieces of wood into any size or shape stretcher a customer needs. They use Tite Joint fasteners, hardware developed for countertop installation, in each corner of the stretcher to allow the artist to expand or shrink the size of the frame to keep the canvas taut. Twin Brooks is only one of a handful of companies making that kind of stretcher in the country, and perhaps the only one using aspen wood, says Polson. The company also makes other types of art supports, crates for shipping its products and painted or gold leaf frames. Polson and Calderwood will stretch the canvas over the frame and prime it with a white acrylic primer if the artist wants. “It’s really cool to take a log and take it all the way through the process by selling them stretched and primed,” Polson says. “It’s a neat way of envisioning this idea of adding value to a Maine product.”

Watch a photo slideshow on Twin Brooks Stretchers

Twin Brooks is the only stretcher company with its own sawmill and kiln, according to Polson, and this vertical integration, plus its willingness to tackle any type of project, allows Twin Brooks to stay cost-competitive, even though its stretchers are more expensive than its readymade competitors. Prices for the stretchers run from about $50 for a small (34-inches by 34-inches) frame to $3,000 and above for massive pieces that have been stretched and primed. Polson and Calderwood also regularly hand-deliver their products to artists, even hopping ferries to North Haven and Islesford. “Others don’t do this level of custom work we do, actually going on site and working with our customers,” Calderwood says.

This over-the-top customer service won over Rockland painter and photographer Eric Hopkins, who was one of Twin Brooks’ first customers. When Hopkins was hired to do a painting for an oddly shaped spot on a couple’s boat, Polson and Calderwood headed out to Wayfarer Marine in Camden to personally measure the space and make a wood panel that would fit precisely. “I like the personal touch,” Hopkins says. “I like to know who I’m dealing with, and they’re very supportive of the artist.”

Polson and Calderwood say they don’t do much advertising, relying mostly on word-of-mouth, the company’s website and the stamp they put on the back of their products. Though Twin Brooks sends its work all over the world, it has also built up a tight network of local connections with artists in the Midcoast area and with Paul and Jula Sampson, husband-and-wife owners of A.E. Sampson. Since Twin Brooks first started making stretchers, the company has paid for A.E. Sampson’s milling services, and over the years the two companies have honed the deal into an efficient, mutually beneficial partnership. A.E. Sampson keeps its price low for its services and picks up Twin Brooks’ wood for free, which saves Twin Brooks from having to buy its own truck. Twin Brooks regularly sends back to A.E. Sampson the bands used to tie the wood into bundles, keeping overhead costs low.

The symbiotic relationship has also helped A.E. Sampson diversify its revenue stream, providing a little more than a quarter of the revenue the company brings in from offering milling services for others, which has become more necessary as the building industry contracts. When Paul Sampson’s father founded the company in 1981, it offered a variety of architectural millwork and had 15 employees. Now, the company focuses only on hardwood flooring and doors and operates with five workers.

“We’re heavily susceptible to hiccups in the building industry,” says Paul Sampson. “We wanted more production that wasn’t building related, and it’s one of the next best industries. Most people don’t consider art an industry, but it’s one of the larger economic factors in the Midcoast.”

Designing their own futures

Polson and Calderwood first partnered up in 1992 after Polson wrote a forest management plan for Calderwood’s 100-acre property, formerly his family’s dairy farm. In return, Calderwood, operating a sawmill at the time, cut some wood for Polson’s home and furniture construction work. Calderwood was a friend of Neil Welliver, the late Lincolnville artist, who suggested the pair make stretchers. They started making stretchers in 1993, working in an old chicken barn at Calderwood’s sawmill and in Polson’s home painting studio. In 2001, a string of major gigs gave Polson and Calderwood the funds they needed to build their current shop on land owned by Calderwood.

One of those big jobs took Polson all the way to the Philippines. After a year-long negotiation with staff at the Lopez Memorial Museum in the Philippines, Twin Brooks made a 12-by-24-foot stretcher frame for a painting that was going to hang in the lobby of a new office building. Polson shipped the stretcher in pieces, then flew to Manila to help museum staff put it together and mount the painting in its new home. In May, Polson is doing a similar job, helping Maine sculptor and painter Jonathan Borofsky disassemble five 12-by-12-foot paintings at his studio in Ogunquit and reassemble them for a show at the Dietch Projects 76 Grant Street gallery in New York City.

At the shop, Polson and Calderwood reminisce over a photo album from the company’s early days, pointing out the plastic tacked onto the ceiling of the old chicken barn to keep the rain out. Through carefully planned growth and a willingness to evolve with customers’ needs, Polson and Calderwood have been able to leave those days behind and prepare for another record year. “This is a big deal for us, going from weeks with no paychecks,” says Polson. “The path we’ve chosen may have taken a little longer, but no one can give us pink slips.”

Mindy Favreau, Mainebiz staff reporter, can be reached at mfavreau@mainebiz.biz.

Read more

Former Wayfarer Marine co-owner Chandler McGaw killed in accident

Comments