Processing Your Payment

Please do not leave this page until complete. This can take a few moments.

- News

-

Editions

-

- Lists

-

Viewpoints

-

Our Events

-

Event Info

- Women's Leadership Forum 2025

- On the Road with Mainebiz in Bethel

- Health Care Forum 2025

- On The Road with Mainebiz in Greenville

- On The Road with Mainebiz in Waterville

- Small Business Forum 2025

- Outstanding Women in Business Reception 2025

- On The Road with Mainebiz in Bath

- 60 Ideas in 60 Minutes Portland 2025

- 40 Under 40 Awards Reception 2025

- On The Road with Mainebiz in Lewiston / Auburn

- 60 Ideas in 60 Minutes Bangor 2025

Award Honorees

- 2025 Business Leaders of the Year

- 2024 Women to Watch Honorees

- 2024 Business Leaders of the Year

- 2023 NextUp: 40 Under 40 Honorees

- 2023 Women to Watch Honorees

- 2023 Business Leaders of the Year

- 2022 NextUp: 40 Under 40 Honorees

- 2022 Women to Watch Honorees

- 2022 Business Leaders of the Year

-

-

Calendar

-

Biz Marketplace

- News

- Editions

- Lists

- Viewpoints

-

Our Events

Event Info

- View all Events

- Women's Leadership Forum 2025

- On the Road with Mainebiz in Bethel

- Health Care Forum 2025

- On The Road with Mainebiz in Greenville

- On The Road with Mainebiz in Waterville

- + More

Award Honorees

- 2025 Business Leaders of the Year

- 2024 Women to Watch Honorees

- 2024 Business Leaders of the Year

- 2023 NextUp: 40 Under 40 Honorees

- 2023 Women to Watch Honorees

- 2023 Business Leaders of the Year

- + More

- 2022 NextUp: 40 Under 40 Honorees

- 2022 Women to Watch Honorees

- 2022 Business Leaders of the Year

- Nomination Forms

- Calendar

- Biz Marketplace

Hancock Lumber's Kevin Hancock on growing after the recession

Photo / Tim Greenway

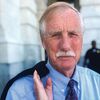

Kevin Hancock, president and CEO of Hancock Lumber, says losing his voice taught him to let others assume leadership roles. He's pictured at the company's Casco site.

Photo / Tim Greenway

Kevin Hancock, president and CEO of Hancock Lumber, says losing his voice taught him to let others assume leadership roles. He's pictured at the company's Casco site.

In spring of 2010, Kevin Hancock was working feverishly to survive the recession. Housing starts in southern Maine had dropped 70%. Hancock Lumber's store sales sank by 45%. At stake was the welfare of 430 employees, three sawmills, 10 stores, 12,000 acres of timberland and a 162-year-old family legacy he had been trusted to steward.

Then one day, Hancock's voice vanished. His painful strained whispers became nearly inaudible. He had developed spasmodic dysphonia, a disorder that causes spasms in the larynx, for which there is no prevention and no cure. In his book, “NOT FOR SALE: Finding Center in the Land of Crazy Horse,” Hancock recounts his serendipitous search for healing via Pine Ridge, an Oglala Lakota reservation in South Dakota. He details how the $140 million company emerged from the crisis healthier than before.

Since 2010, sales have grown on average by 8% each year. Employee compensation has risen by more than 3% each year. The average work week has shrunk from 47 hours per week to 41. Twice Hancock Lumber was named one of Maine's Best Places to Work.

Hancock sat down with Mainebiz to discuss the Casco-based company's transformation, and why the loss of his voice was a blessing. An edited transcript follows.

Mainebiz: How did losing your voice change your role?

Kevin Hancock: I learned that leadership is about doing less, not more. It was letting people who have responsibility own their issues and opportunities to learn and make decisions. Before, I was deeper into processes, like mill budgets, negotiating with key customers and strategic planning. I'm still involved. But information comes from the front lines, where the products get made and the customer gets served.

MB: Isn't that risky?

KH: We have good transparency. If a key metric like safety or productivity is at risk, everybody sees it, and feels a responsibility to fix it. There's more accountability. In the traditional model, top executives hold all the information, explain the problem and determine the solution. The people actually doing the work just wait to hear. They don't have a sense of ownership … But putting the strongest voice as far from corporate as possible has lots of benefits.

MB: How did that change impact daily operations performance?

KH: We started offering employees incentives to reduce order 'rework' because of errors in product, price or amount. As a result, rework dropped by 66%. We also examined journey value — the value of the product on a truck when it leaves our yard. There was a lot of unused capacity on trucks. We did more planning, and worked with contractors to get bigger orders on trucks. We offered incentives to increase journey value and since we did it nearly doubled … We've been setting records for sales growth, safety, accuracy and profitability. I don't think that's a coincidence.

MB: What role does work-life balance play?

KH: Work should push people to grow, but it shouldn't be emotionally or physically draining. Often it is. People shouldn't have to spend the whole weekend resting just in order to do it again next week.

MB: How did you achieve that?

KH: Typically people work overtime because of waste, inefficiency or extra compensation. We created incentives that allow everyone to share the economic benefits of improved efficiency and accuracy. We also raised base pay. Between the two, compensation for employees increased, while work weeks got shorter. The work is more accurate and less stressful. We don't feel this makes work easy or that it dramatically changes people's financial positions. But, if people can work just a little less and earn a little more, that's progress.

MB: How is your voice now?

KH: My voice comes and goes. I used to talk all day. Now I listen most of the day. I email more. I'm getting treatment. But losing my voice was a blessing. If someone had a magic wand so it never happened, I'd say 'No thank you.' When I first acquired this, I was scared. I wondered whether I would be able to do my job. Now I see that it makes me better at my job.

Read more

Comments