Processing Your Payment

Please do not leave this page until complete. This can take a few moments.

- News

-

Editions

-

- Lists

-

Viewpoints

-

Our Events

-

Event Info

- Women's Leadership Forum 2025

- On the Road with Mainebiz in Bethel

- Health Care Forum 2025

- On The Road with Mainebiz in Greenville

- On The Road with Mainebiz in Waterville

- Small Business Forum 2025

- Outstanding Women in Business Reception 2025

- On The Road with Mainebiz in Bath

- 60 Ideas in 60 Minutes Portland 2025

- 40 Under 40 Awards Reception 2025

- On The Road with Mainebiz in Lewiston / Auburn

- 60 Ideas in 60 Minutes Bangor 2025

Award Honorees

- 2025 Business Leaders of the Year

- 2024 Women to Watch Honorees

- 2024 Business Leaders of the Year

- 2023 NextUp: 40 Under 40 Honorees

- 2023 Women to Watch Honorees

- 2023 Business Leaders of the Year

- 2022 NextUp: 40 Under 40 Honorees

- 2022 Women to Watch Honorees

- 2022 Business Leaders of the Year

-

-

Calendar

-

Biz Marketplace

- News

-

Editions

View Digital Editions

Biweekly Issues

- April 21, 2025 Edition

- April 7, 2025

- March 24, 2025

- March 10, 2025

- Feb. 24, 2025

- Feb. 10, 2025

- + More

Special Editions

- Lists

- Viewpoints

-

Our Events

Event Info

- View all Events

- Women's Leadership Forum 2025

- On the Road with Mainebiz in Bethel

- Health Care Forum 2025

- On The Road with Mainebiz in Greenville

- On The Road with Mainebiz in Waterville

- + More

Award Honorees

- 2025 Business Leaders of the Year

- 2024 Women to Watch Honorees

- 2024 Business Leaders of the Year

- 2023 NextUp: 40 Under 40 Honorees

- 2023 Women to Watch Honorees

- 2023 Business Leaders of the Year

- + More

- 2022 NextUp: 40 Under 40 Honorees

- 2022 Women to Watch Honorees

- 2022 Business Leaders of the Year

- Nomination Forms

- Calendar

- Biz Marketplace

How early childhood stress could lead to costly adult illnesses

Courtesy / Eager Eye Photography

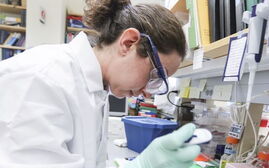

James Coffman, a developmental biologist at MDI Biological Laboratory, is studying how chronic exposure to a stress hormone early in life could lead to costly adult diseases including cancer and heart disease.

Courtesy / Eager Eye Photography

James Coffman, a developmental biologist at MDI Biological Laboratory, is studying how chronic exposure to a stress hormone early in life could lead to costly adult diseases including cancer and heart disease.

Courtesy / MDI Biological Laboratory

Zebrafish are helping MDI Biological Laboratory developmental biologist James Coffman understand how stress in young fish relates to disease later in life. The stress and immune system in zebrafish are essentially the same as in humans.

Courtesy / MDI Biological Laboratory

Zebrafish are helping MDI Biological Laboratory developmental biologist James Coffman understand how stress in young fish relates to disease later in life. The stress and immune system in zebrafish are essentially the same as in humans.

We’re all familiar with the short-term stress caused by election politics or our favorite sports team, but researchers at the MDI Biological Laboratory are looking at how chronic exposure to stress early in life may lead adults to be more vulnerable to costly diseases linked to chronic inflammation like arthritis, cancer and diabetes.

Diabetes alone cost Americans $245 billion in 2012, with $176 billion in direct medical costs and $69 billion in reduced work productivity, according to the American Diabetes Association. Medical costs for cancer are expected to hit $158 billion in 2020, up 27% over 2010 (both in 2010 dollars), according to the National Institutes of Health.

While scientists have known for a while about the stress-inflammation-disease link, they don’t know exactly how stress incites inflammation and, in turn, disease. Developmental biologist James Coffman and his colleagues at MDIBL in Bar Harbor are studying the zebrafish, which they said has essentially the same immune system and stress response as humans, to answer that question.

The researchers treated zebrafish embryos with cortisol, a type of steroid hormone known as a glucocorticoid that is linked to developmental programing and that occurs naturally in the body. They looked at the effects five days later as the embryos grew into larvae and then later as the larvae grew into adults. They found that the treated fish had higher levels of cortisol and glucocorticoid signaling. Those higher levels led to a defense response by the body, which in turn caused inflammation.

The researchers concluded that chronically elevated glucocorticoid signaling early in life causes a predisposition to inflammation in adults, thus potentially leading to disease.

They published their research results in the journal “Biology Open.”

A modern problem

“Inflammation is a normal response to protect the body from harmful stimuli, but if the inflammation is chronic, it is destructive and can cause disease,” Coffman explained. “Chronic psychosocial stress increases the level of cortisol circulating in the body, and if this happens early in life it can influence how the body develops.”

He added, “So our research helps explain why young children who experience chronic psychosocial stress, due for example to low socioeconomic status, economic insecurity, abuse or neglect, are more vulnerable as adults to health problems associated with inflammation and immune dysfunction.” He told Mainebiz that the stress can even be felt prenatally if the mother is in an abusive situation or lives in poverty.

“It’s a social issue,” Coffman explained, adding that chronic stress is a modern problem that is on the rise.

Fighting stress

But there are some potential pharmacological and behavioral treatments that could help counteract the effects of stress.

MDIBL President Kevin Strange said, “Research in this emerging field suggests that interventions to mitigate the effects of early-life stress could one day lead to significant improvements in public health.”

Coffman said there are other hormones in the body that can help fight the effects of chronic stress, such as oxytocin, also known as the “love hormone,” because it is secreted during pleasant social interactions like hugs. Nursing mothers especially have high levels of oxytocin.

Coffman became interested in studying the impact of stress on aging when he noticed that chronically stressed people often age faster.

He said the next step for the researchers is to identify and study the ways chronically elevated cortisol alters the immune system’s development.

The research was funded by Institutional Development Awards from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health.

Read more

MDI Bio Lab inspires art for a visceral experience of science

Two Bar Harbor labs get separate NIH grants topping $1.67M to study nerve damage

MDI Bio Lab scientists score patent for heart repair medicine

Comments