Processing Your Payment

Please do not leave this page until complete. This can take a few moments.

Maine brewers find ways to adapt to CO2 shortage

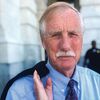

Photo / Tim Greenway

Patrick Rowan, owner of Woodland Farms Brewery in Kittery, says the firm’s cost of carbon dioxide has quadrupled.

Photo / Tim Greenway

Patrick Rowan, owner of Woodland Farms Brewery in Kittery, says the firm’s cost of carbon dioxide has quadrupled.

Higher carbon dioxide prices are forcing Maine breweries to get creative.

While not all Maine beer brewers are feeling the squeeze of the ongoing, nationwide carbon dioxide shortage, others have altered their production processes to more efficiently use the gas.

Carbon dioxide is often used throughout the beer-making process, whether to aid in carbonation, pressure-assisted tank decanting or clearing oxygen from tanks. Given that it’s one of the greenhouse gasses blamed for the climate crisis, it may seem counterintuitive that there isn’t enough carbon dioxide floating around for breweries to use.

But while some companies are pulling the gas out of the atmosphere to mitigate climate change — and some of that is used for beverage carbonation — atmospheric carbon removal isn’t currently mainstream. Instead, Will Gentry, the president of gas supplier MaineOxy, says most of the carbon dioxide provided to breweries is a byproduct of three activities: petroleum refining and ammonia or ethanol production. And those activities slowed during the pandemic, meaning less available captured byproduct for the brewing industry, he explained.

“Now we’re telling our customers to have enough on hand for six to eight weeks, so if there is a shortage, you can actually get through it and you’ll have enough product to get to move ahead” with beer production, Gentry says.

Once supplies began tightening, companies like MaineOxy had to reduce their clients’ allocations and charge more for what was delivered, too. Gentry declined to share how his company’s year-over-year carbon dioxide charges changed, citing business competitiveness concerns.

However, the producer price index published by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that carbon dioxide prices within the industrial gas manufacturing industry consistently rose throughout the pandemic, soaring in the summer of 2022.

Numerous Maine breweries told Mainebiz that their prices have shot up, with some feeling the pain more sharply than others. In an email, Patrick Rowan, owner of Woodland Farms Brewery in Kittery, suggested that the matter has reached levels of “price gouging.”

“We’ve seen our CO2 prices quadruple in the last 24 months, and we’ve been rationed twice to 50%” allocation from before the shortage, says Rowan, using the formulaic shorthand for carbon dioxide.

To navigate the challenge, has forced his team to get “seriously creative” and “generally watch every last drop we use” to navigate the new terrain.

David Love, the sustainability manager of Maine Beer Co. in Freeport, says their carbon dioxide prices have been contractually locked in. But while they were “one of the luckier breweries, where we never ran out of CO2,” their allocation and the regularity of deliveries diminished.

Side By Each Brewing Co. in Auburn was paying roughly 46 cents per pound of carbon dioxide in the fall of 2019, “before COVID and all the madness started,” according to owner-brewer Ben Low.

A year later, the cost had risen to 53 cents per pound, including a force majeure charge. Now, they’re paying 66 cents per pound — even with the force majeure charge dropped.

“That’s almost a 50% increase, which is a lot, and the other charges associated have gone up as well,” Low says, detailing other charges on his carbon dioxide invoices he says have tripled, such as delivery. “It’s a pretty big price hit.”

‘I’m not scared anymore’

The shortage has lasted so long that some brewers, like Fogtown Brewing Co. in Ellsworth, switched providers for more reliable deliveries. At first, the shortage didn’t affect Fogtown strongly because the pandemic lock-down measures prevented it from opening their doors.

“It didn’t matter that we weren’t making [beer], because we didn’t have a market, but that continued even after reopening” says Fogtown owner Jon Stein, noting how bulk tanks wouldn’t arrive for “weeks and weeks on end.”

Like many breweries that Mainebiz interviewed, Fogtown looked at alternative methods of production to reduce their demand for carbon dioxide, including natural fermentation, also known as spunding. That essentially means trapping the carbon dioxide created during the fermentation process, which absorbs into the substance becoming beer.

While that might seem a simple change, Stein says the “timing is a bit tricky” and that “it’s a hard process, because if you do it too early, then you’re starting to trap in essentially all these … weird, volatile flavor compounds, and you usually want them to bubble off so that you don’t taste them in the beer later.”

“But if we’re doing it really well, we can save around 20% CO2 volume per batch,” he added. Another bonus — his team thinks there’s an improved flavor and “mouthfeel” with properly executed natural carbonation.

The achieved efficiency helps Stein feel confident about weathering the supply shortage. “I’m not scared anymore about providers running out of CO2, but it does still save a lot of money because CO2 is only getting more expensive,” says Stein.

At Nonesuch River Brewing in Scarborough, owner and brewery operations director Michael Schuler says his team also switched to natural fermentation, reducing exposure to the higher prices.

“We’ve used about 25% less CO2 this year, however our supplier has run into cost issues that they’ve passed on to the consumer, which is us,” Schuler explained. “From a dollar perspective, it doesn’t seem like we’ve saved any money, but we’ve used less CO2.”

Nonesuch only partially carbonates their brews via natural fermentation because of the additional time a batch needs to spend in the fermenter to fully complete that process. That extra time takes away from the brewery’s ability to make more new batches.

Nonetheless, he says, “if we would have used the same amount that we used a couple of years ago, we would have seen at least a 25% rise in cost.”

‘Conserve as much’ as possible

Schuler says another way breweries are making the most of the carbon dioxide they can get their hands on is by switching to other inert gasses that are more available for packaging and purging tanks of oxygen before adding beer, since “oxygen is the killer of all beer.”

At Nonesuch, he says “we started to use more nitrogen to push liquids around in the brewery instead of CO2, so that we could conserve as much of the CO2 as we could for the things that we really needed it for.”

Love says that Maine Beer Co. has also begun using nitrogen for the same types of processes, but added there’s a sustainability incentive to make the switch, too, because nitrogen is “incredibly abundant and it’s also locally available” because of a refinery in Kittery.

“The actual carbon footprint of that gas, which is already relatively low compared to CO2, is going to be even lower because it’s coming from somewhere so close.”

Delivering ‘the biggest savings’

At Sacred Profane, a Biddeford brewery that opened its doors in September, brewery operations director Michael Fava and his team had the advantage of being able to design the brewery around “processes that are as efficient as possible, right from the jump.”

In addition to strategies more commonly employed by other breweries, Sacred Profane opts to serve beer right out of copper serving tanks, suspended from the ceiling over the bar in an “actually quite beautiful” way, Fava says. That, he says, delivers “the biggest savings.”

But the brewery also implements bag-in-tank technology, which Fava calls a newer type of set-up. Essentially, a big plastic liner is used to shield the beer from the tank, allowing a brewery to use compressed air instead of an inert gas to push the beer out of the system.

Fava says that even without the heightened costs and lessened availability, the bag-in-tank system would be beneficial to improve the overall drinking experience.

At a small number of breweries, innovative carbon recapture technology has been deployed to further reduce demand for new shipments. But many can’t afford to install such systems, according to Rowan.

“Ideally we’d have a CO2 recapturing system in place, but they are prohibitively expensive for all but the largest of breweries,” he says.

Love says that Maine Brewing Co. commissioned and installed its system in November, although the idea had been kicking around in their heads for a while.

“We had had multiple quotes, we had gone back-and-forth and says, ‘Hey, is this the year where we finally do it?’” says Love. “Then everything happened with the CO2 market, and suddenly we are in a good spot to really invest this time and money to make this happen.”

0 Comments