Processing Your Payment

Please do not leave this page until complete. This can take a few moments.

Maine's lobstering industry wins temporary halt to offshore fishing ban

File photo / Laurie Schreiber

The lobster industry got a significant win when a district court judge granted an emergency restraining order to block the closure of a large swath of offshore fishing ground.

File photo / Laurie Schreiber

The lobster industry got a significant win when a district court judge granted an emergency restraining order to block the closure of a large swath of offshore fishing ground.

With just two days to spare, Maine’s lobster industry on Saturday won an emergency motion to stop an impending seasonal closure of lobster fishing in federal waters off the state's coast.

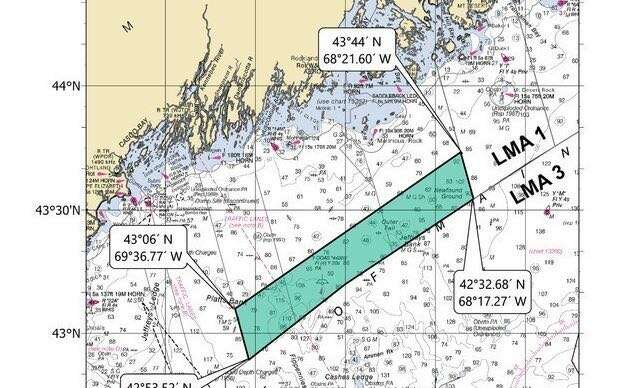

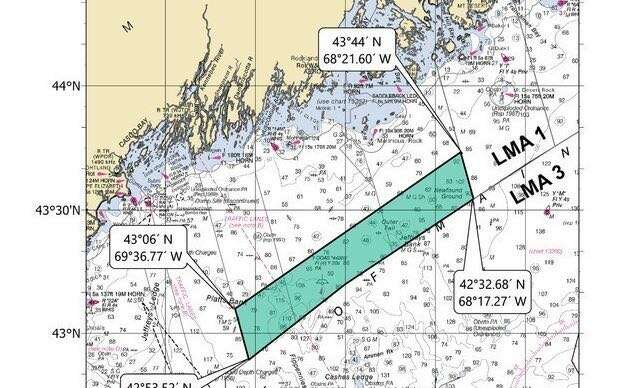

The closure of 967 square miles was due to go into effect Monday. On Oct. 16, U.S. District Judge Lance Walker issued a temporary restraining order blocking the ban.

Walker wrote that the federal government, responsible for setting the closure as a method to keep endangered North Atlantic right whales safe from lobster fishing gear, “lacks any traditional evidence that Maine fishing gear has been responsible for the take of a right whale in recent years.”

Industry vs. government

Trenton-based Maine Lobstering Union, Fox Island Lobster Co. of Vinalhaven and its co-owner Frank Thompson, and the Damon Family Lobster Co. of Stonington filed the motion last month in the U.S. District Court in Bangor against the federal Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and National Marine Fisheries Service.

The lawsuit was filed by the Portland law firm of McCloskey, Mina, Cunniff & Frawley LLC.

The federal government estimated 62 federally permitted fishermen from Stonington to Boothbay Harbor would be affected by the closure, which was scheduled to take place from October to January and includes the fishery’s most active period.

The area is about 12 miles off the southern Maine coast.

Expected losses

According to the Maine Lobster Union motion, the restricted area would result in significant losses.

Although the federal rule estimated that 62 vessels would be affected by the closure, the union’s motion said actually double that number, 123 vessels, would be affected. The lobster boats mainly work out of Stonington and Vinalhaven, the Maine Lobster Union said.

Damon, in Stonington, sells about 4 million pounds of lobster annually, about a quarter of which comes from the restricted area between October and January.

Fox Island Lobster, in Vinalhaven, buys at least 1 million pounds of lobster per year between October and January from 50 to 60 boats, most of it coming from the restricted area.

About half of Thompson’s income would be lost as a result of the restriction. In addition, he would be forced to fish further north, in far more dangerous conditions in order to avoid gear conflicts with other lobstermen fishing near the area.

The union owns Lobster 207 LLC in Trenton, which operates a wholesale and retail business. It would stand to lose about 4 million pounds of lobster for every season the restricted area remains in place, which could put the company out of business, according to the motion.

“With the loss of the millions of pounds of lobsters that will result from the closure area, many bait dealers, wholesalers and suppliers will go out of business,” the motion said.

‘Not exactly transparent’

Walker said the scientific record of known large whale entanglements and vessel strikes in the area between 2010 and 2019 “offers little to support” an outright closure.

Although there have been whale entanglements elsewhere in the Gulf of Maine, none were within the designated area, he wrote.

The available information about whale distribution “itself is controversial and not exactly transparent,” he continued. He called the statistical modeling methodology that was used as the basis for the closure “markedly thin.”

Walker said the lobster industry’s concerns about the economic effects of the regulation are substantial enough to support relief.

The federal government has cited the annual cost to the industry of the measure as between $9.8 and $19.2 million, representing 1.5% to 3% of 2019 landings.

But Walker said the brunt of those costs will be borne by two of southern Maine’s foremost fishing communities.

"Given that the cost of the closure also will be born by two communities — Vinalhaven and Stonington — it is hard to cast such losses as anything other than ‘significant,’” he wrote.

“Without trivializing the precarity or significance of the right whale as a species, I find that the certain economic harms that would result from allowing this closure to go into effect outweigh the uncertain and unknown benefits of closing some of the richest fishing ground in Maine for three months based on a prediction that it might be a hotspot for right whale entanglement,” he said.

Noting that the situation pits “a culturally and economically valuable fishery against the preservation of an equally iconic endangered species,” Walker ruled the closure could not be enforced pending further order of the court.

‘Critically important’

“This victory by the Maine Lobstering Union is a significant step in protecting one of Maine’s most precious industries – lobstering,” Alfred Frawley, the attorney who represented the Maine Lobstering Union in the case, said in a news release. “The regulations proposed by federal agencies would have had a chilling impact on communities throughout Maine.”

In an amicus brief filed with the motion, the Maine Lobstermen’s Association, headquartered in Kennebunk, said the swath represents “critically important” Maine lobster fishing grounds.

“This closure will do nothing to protect right whales, but it will cause unnecessary financial harm to Maine lobstermen, their families, and the economy of Maine,” Patrice McCarron, the association’s executive director, said in a separate release. “The MLA remains committed to doing our part to recover right whales, but this closure is essentially useless even as a small step toward recovery for the species.”

According to the amicus brief, there has never been a single documented or observed instance of a North Atlantic right whale gear entanglement in the closure area. Lobstermen who traditionally fish the area “will suffer significant, immediate financial harm” if the closure goes into effect, the brief says.

The seasonal closure bans vertical rope that stretches from lobster traps on the ocean’s bottom to surface buoys. The restricted area was scheduled to remain closed through Jan. 30, 2022. Fishermen would be able to apply for special permits to test ropeless fishing gear in the area.

Suite of regulations

The closure off the Maine coast, and others off the Massachusetts coast, are part of a federal plan, announced Aug. 31, to reduce mortalities and serious injuries from fishing gear to North Atlantic right whales, humpback whales and fin whales. The plan also includes gear modifications that will take effect May 1, 2022.

The plan has a goal to nearly eliminate risk to right whales by 2030.

Conservation groups have said the plan isn’t enough.

In pending litigation, Center for Biological Diversity v. Ross, filed in the U.S. District Court in D.C., a consortium of environmental advocacy groups says the plan needs to be made more stringent.

Earlier this month, Conservation Law Foundation in Portland, said the closure would reduce the chance that whales become entangled in lobster gear in the Gulf of Maine.

“There is a limited window of time to save critically endangered right whales,” Erica Fuller, a senior attorney with the foundation, said in a separate release. “Closing certain areas to fishing when high numbers of right whales are present is the most effective way to reduce risk.”

The focus of the rule is on North Atlantic right whales because of their status as a critically endangered species, with only an estimated 368 left in the world.

The goal is to reduce or eliminate the number of vertical lines the whales might encounter along their migration routes.

In a statement yesterday, U.S. Rep. Jared Golden, D-2nd District, said Walker’s decision to block the closure “is a positive signal that the voices of Maine lobstermen are being heard. For the first time in this regulatory process, the concerns of lobstermen were weighed fairly and as a result we have a ruling grounded in common sense and the public good.”

Maine has a fleet of 4,800 individually owned and operated lobster fishing vessels that support tens of thousands of jobs. In 2020, Maine's lobster catch was valued at $405 million.

0 Comments