Processing Your Payment

Please do not leave this page until complete. This can take a few moments.

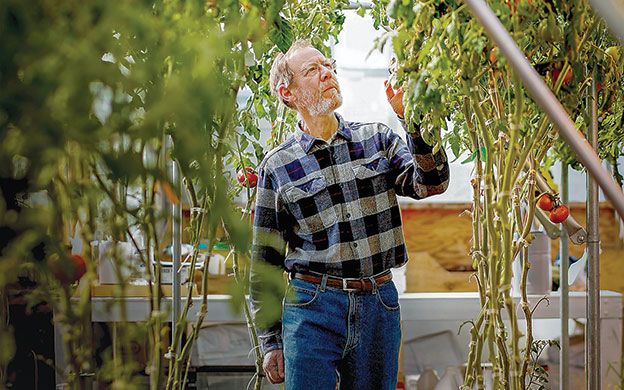

Plants aren't the only thing growing at Johnny's Selected Seeds

Walking around Johnny's Selected Seeds' research farm, one expects to see rows and acres of commercial seed-producing plants. But most of the seeds sold by Johnny's are produced in the parts of the world where they grow best, and then are harvested by Johnny's.

At the research farm, company founder and Chairman Rob Johnston Jr. continually probes and tests to produce seeds that could potentially grow into plumper tomatoes or tastier lettuce. During the 2015 growing season the farm grew nearly 140,000 seedlings on its 29 miles of formed beds.

For testing, new breeds grow alongside existing ones to compare the look, taste and other features, says Johnston, who founded the company in 1973. He now spends most of his time working to create better seeds, but also relaxes part of the year with his wife at their residence in France.

“Plant breeding and genetics is an introverted vocation,” says Johnston, adding that it suits him to be in a nursery with earth under his feet.

“Most of our seeds [for sale] aren't grown here,” adds David Mehlhorn, vice president of sales and marketing at the company's Fairfield headquarters. Johnny's also has a customer fulfillment center and retail store in Winslow and the research farm in Albion. “They're grown all over the world in the best areas environmentally to grow them, the most productive places.”

Yet, in Maine, Johnny's is a beehive of activity. The company packs 1.5 million units of seeds annually, primarily by hand. It sells about 1,827 products, including seeds, tools, fertilizers, insecticides and fungicides. It also sells about 433 organic varieties.

It uses about 200 different vendors to sell seeds, supplies and tools that it makes itself or resells other brands. Though it sells online and through its retail store, Johnny's is best known for its catalogs, which contain about 1,500 varieties of seeds. This season, from November 2015 to February 2016, Johnny's mailed 1.1 million catalogs.

Each year it adds about 200 new seed varieties to the catalog, and about another 200 are retired.

Revenue is about $40 million, and the growth rate has been about 8% in the last couple years, Mehlhorn says.

Mehlhorn says Johnny's competes with about 20 regional seed companies, including Mount Vernon, Wash.-based Osborne Seed Co., rather than the giants like Warminster, Pa.-based W. Atlee Burpee & Co. Most of the Johnny's business, Johnston says, is in the United States, but it also exports products to 50 countries.

'Back to the land' redux

Johnston started the company in 1973 at age 22 with $500 in savings in a New Hampshire farm attic during the back to the land movement, which has resurfaced in some ways in the recent farm-to-fork movement and boom in avid home gardeners, who account for about 25%-30% of Johnny's sales. The other 70% goes to commercial customers, Johnston says.

A mathematics and chemistry major at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst, Johnston dropped out after two years to work first at a natural food store in Providence, R.I., and in 1972 on a communal truck farm in southern New Hampshire, where he got his first experience with large-scale farming and the seed business. He began focusing on seeds because a customer in New York wanted specialty produce.

He named his first small company Johnny Appleseed after the American pioneer nurseryman, and in the fall of 1974 moved temporarily to use farmland friends offered in Dixmont. Johnston sent out the first seed catalog from his parents' home in Massachusetts in 1974. The following year he moved to the 120-acre former dairy farm in Albion.

Johnston's company quickly became known for its simple white seed package and the catalog, which included growing information and variety descriptions that he wrote. The retail store in Winslow opened in 2003, the company's 30th anniversary.

“I'm interested in having a face on the food. Supporting regional agriculture is a real opportunity for market gardeners to produce food year-round for clientele and grow it through the winter,” Johnston says, using new technologies and hoop houses that extend growing seasons.

Employee owned

The company now employs about 210 full-time and seasonal workers. In 2005, Johnny's formed an Employee Stock Ownership Plan, or ESOP, and the company became fully owned by employees in 2012.

“I wondered what's going to happen with the company when I grow old,” says Johnston. “An ESOP is a graceful transition. One of the risks is that an organization can then become too conservative. I'm careful, but I am investing in a few businesses, including plant breeding and tools. I'm not investing too fast, as it stresses the organization too much.”

Employees can join the ESOP at age 21 and if they've been working at the company at least 1,000 hours per year. They are vested 20% each year until they reach 100%, says Cheryl Wilson, operations lead in the distribution center and one of the ESOP owners.

“There certainly is more vested interest in how a company performs and it has a unique culture,” adds Mehlhorn. Employees can nominate and vote for board members. There's a sign-up list for three employees to sit in on and audit board meetings.

Exacting work

A walk through the retail store and distribution center is the complete opposite of the peace and quiet in the research center. Seasonal and full-time workers fill the center, moving constantly to fill orders. High season runs from January through March, when farmers and gardeners are planning their crops.

Everything in the distribution center is measured in some way, from the weight of the seeds in a packet to the number of bulk-sale bags on a palette to the distance of the most frequently sold items from the warehouse shipping door.

High-volume sales items also are kept on middle shelves to help ease the strain of employees bending over to lower shelves, Wilson says. The distribution center handles about 200 different vendors of tools and seeds

“We weigh everything,” she says. “And we have an internal lab to meet USDA and FDA standards.” Temperature and humidity also are strictly controlled to keep the seeds from spoiling.

Order turnaround is fast. If an order comes in by 2 p.m., it ships the same day.

About 1.5 million units of seeds are packed per year, primarily by hand. Depending on the size of the seed, packet-stuffers use Yankee ingenuity to find the best container to help them accurately fill a packet, whether that is a Pampered Chef adjustable measuring spoon or an ammunition refill kit for the smaller flower seeds.

Meeting changing demands

The farm-to-fork movement also created demand for more fresh vegetables and fruit year-round, and that in turn is causing farmers to look for ways to extend their growing seasons using different crops or hoop houses, and it is causing seed companies like Johnny's to develop varieties that are more hardy in the cold.

“Extending the season by overwintering in a hoop house is a trend, so crops that grow in the winter or lie dormant [can be revived in the spring] and don't die,” says Mehlhorn. “The hoop houses structures are getting better, and we are doing some seed breeding for cold tolerances.”

He says more and more greenhouse operations are remaining open in New England and across the country in colder zones.

Part of the push, he says, is from restaurants that want fresh produce off season.

Kale, which has a long growing season, has been hot for a couple years, he says. Brassicas — cabbages, mustard plants, broccoli and cauliflower — are popular in northern Maine.

“The culinary places are pushing for new foods that can grow in a cool, but long season,” he says. “We're always trying to find something better. And we now work with more than 300 vendors all over the world.”

Products typically are selected for flavor, but other traits in breeding include shelf life, he says, noting that shipping can take away from flavor. Another trait is the reliability of the seed growth under varying conditions.

“People are getting more concerned and active about 'how do I keep this land productive,'” he says. “So they want quality seeds and to learn the best growing practices.”

Mehlhorn expects Johnston to be active in the business forever. The company is searching for a new general manager.

“Rob has a unique perspective on the company and market segment,” says Mehlhorn. “He has a really strong mission purpose and helps keep a focus on customers and providing value to customers to make them more successful as growers.”

Mehlhorn says Johnston also is very active with customer feedback. Says Mehlhorn, “He's very attuned to what people feel about the company.”

Says Johnston, “Continuity is the success in this organization. Helping families and friends and communities feed one another by producing good products is important. We are in the same work together.”

Read more

So you’ve set up your ESOP. Now what?

Comments