Processing Your Payment

Please do not leave this page until complete. This can take a few moments.

Rural brewers craft a niche by tapping into a new business model

Photo / Jim Neuger

Abraham Lorrain, left, and his dad, Paul Lorrain, founded Funky Bow Brewery & Beer Co. They’re pictured at the brewery in Lyman. Paul Lorrain’s fiddle lessons inspired the name.

Photo / Jim Neuger

Abraham Lorrain, left, and his dad, Paul Lorrain, founded Funky Bow Brewery & Beer Co. They’re pictured at the brewery in Lyman. Paul Lorrain’s fiddle lessons inspired the name.

Funky Bow Lane won’t show up on Google Maps, a dirt road within a 25-acre property in Lyman that’s home to a craft brewery of the same name.

Paul Lorrain, 69, whose fiddle lessons inspired the name, owns Funky Bow Brewery & Beer Co. with his 36-year-old son, Abraham Lorrain. The music motif is incorporated into the logo and product names like Jam Session IPA and G-String.

Seeing father and son good naturedly rib each other and joke with beers in hand, it’s hard to fathom they didn’t speak for seven years. Then after getting a letter from Abraham who was about to move to California to pursue a Ph.D. in fermentation, Paul offered to build a brewery on his land and the two started a business in March 2013.

“Brew me a beer I can sell more than once,” Paul told his son.

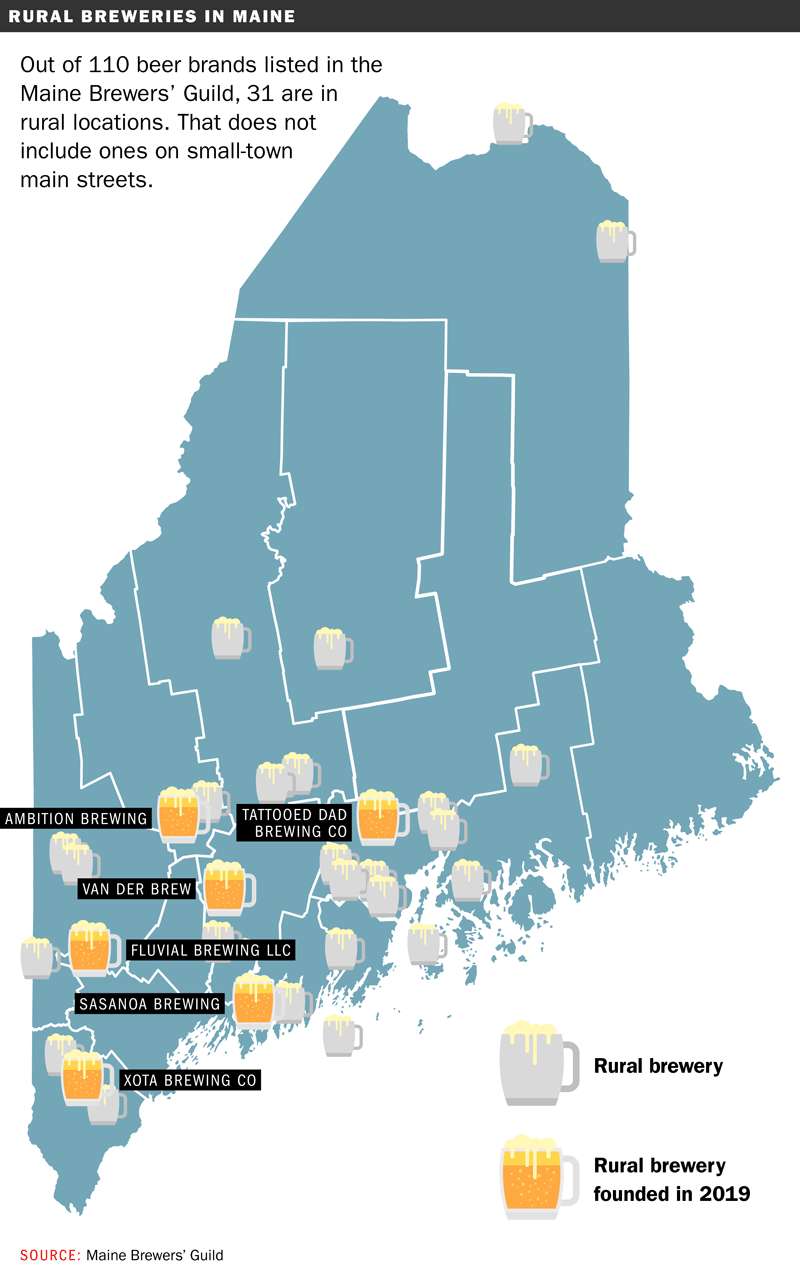

Funky Bow is one of 31 home-grown rural brands out of 110 total in the Maine Brewers’ Guild. Craft brewers — and destination taprooms — in remote spots are sprouting up so fast that the Guild launched a digital travel planner this spring to guide visitors, while The Maine Brew Bus offers beer-and-birding road trips such as “Shorebirds and Steins” and “Fall Ducks and Draughts.”

“We’re always looking for ways to get more of Maine’s breweries not centered around greater Portland,” says Maine Brew Bus general manager Don Littlefield. There are more to choose from all the time.

Maine’s newest rural brewers include Sasanoa Brewing on a Westport Island farm whose creations are already making an impression on the beer world, Tattooed Dad Brewing in Jackson, XOTA Brewing in Waterboro, Ambition Brewing in Wilton, Van der Brew in Winthrop and Fluvial Brewing in Harrison, which is getting ready to open later this month.

Craft industry disruptors

In part, the growth in rural breweries is sparked by craft’s overall popularity, with all 16 Maine counties now having at least one craft brewer, as shown in a January report by the University of Maine. It found that the craft sector added $260 million to Maine’s economy in 2017.

As a predominantly rural state, Maine has become fertile ground for budding entrepreneurs opening breweries and tasting areas on farms and properties where they live, meaning lower startup costs and fewer barriers to market entry than in a city.

Many of today’s rural brewers start out as home-kit hobbyists, surprised to get help from established players as they get their business off the ground. Some choose to stay small, local community gathering places, while others are expanding their brand reach through bottling, canning and “tap takeovers” at pubs and restaurants. That’s getting harder as the market gets more crowded.

Regardless of what path they choose, country brewers are shaking up the industry and traditional urban hipster tasting-room culture by luring families, older clients and even non-drinkers with live music, games, recreational activities and lodgings.

“Giving customers more than just a beer is increasingly important to lots of breweries,” notes Bart Watson, chief economist of the Boulder, Colo.-based Brewers Association, a nonprofit group representing the industry nationwide. “It isn’t unique to rural breweries, but it may be more important to them because they need a certain percentage of customers to have a strong reason to come.”

Maine Brewers’ Guild executive director Sean Sullivan has a similar observation, noting that rural brewers “are taking the best aspects of the pub and brewery culture and putting it back into the community … Going to these small breweries on a Friday or Saturday night, it’s about a lot more than drinking, a lot more than food, it’s a place where people feel comfortable bringing their kids or meeting their friends and parents. That kind of intergenerational comfort is really interesting, and I can’t think of other places like that.”

Sullivan attributes the rural-brewery growth momentum to a combination of factors, including owners’ pride in serving their communities, like the town baker or mechanic.

“It’s an honest pride and it’s pride of service,” he says. “Small-town America has professions that fill certain roles, and brewing is one that’s coming back.”

Down on the farm

In the countryside, breweries are strongly rooted in agriculture and farm life.

At Skowhegan’s Bigelow Brewing Co., for example, owners Jeff Powers and Pamela James-Powers work with 30 local farmers and businesses to run the brewery and kitchen. They also grow the hops that’s used in two seasonal beers and pumpkins used in autumnal releases like Witch’s Tit Pumpkin Ale.

Bigelow, housed in a former horse barn and open year-round, has far exceeded its owners’ expectations since opening to the public in September 2014, with a grand opening that attracted 300 people. As with many others, it’s found a winning combination in beer and pizza, made in a wood-fired oven using spent grains, or leftover malt and other materials from making beer, and flour from Maine Grains. It also uses only malts grown and malted in Maine.

As business has grown, it’s expanded into canning, which now accounts for 60% of production. Total output has jumped from 64 barrels in the first year to 900 last year, and already 450 barrels in the first three months of this year.

Pamela, a former middle-school language arts teacher, supervises the kitchen and tap room, while Jeff, who’s still full-time at a paper mill in Rumford, recently handed over head-brewer duties to a new hire. They employ six people full-time and four part-time.

“It was going to be a man cave for my husband,” Pamela says. “It’s turned into way more than that.”

One day, Joy and Jim Bueschen hope to emulate Bigelow’s success at Turning Page Farm, a goat farm in Monson that makes cheese and other products from the milk and recently branched out into beer.

“Bigelow is what we want to be when we grow up,” says Jim, who learned brewing with fellow expats in Munich, Germany, before the couple moved to Maine in 2016 for a change of lifestyle.

Jim got his brewer’s license last year, and within three weeks the couple opened an outdoor beer garden. This summer, they’re building an indoor tasting room in a passively heated greenhouse to extend their season.

Fluvial at the starting gate

In Harrison at Fluvial, Lisa and Shaun Graham are putting the finishing touches on a tasting room they aim to open by the end of June.

Shaun, a military veteran who formerly worked in hedge-fund accounting, got into craft brewing from a kit he received as a gift while recovering from a shoulder injury, while Lisa is a self-employed occupational therapist who works with children with disabilities during the school year.

Parents of two small children, the couple decided to build a beer business on their 40-acre property to get in more quality family time — now Shaun works here instead of commuting to Portland.

They’re on a one-barrel system with two- and three-barrel fermenters, and the plan is to stay small and community-focused.

“Our goal,” Lisa says, “is to create that third home for people. You have your own home, you have your workplace, and we need a local hangout that is family-friendly and comfortable. There’s not a lot of other businesses here in Harrison, so we’re really excited to do that.”

Outdoor enthusiasts who met through white-water rafting, they chose a name and logo to reflect that activity, and plan to make outdoor recreation a core part of what they offer visitors as they make the most of land that overlooks a scenic ridge and abuts 300 acres owned by Loon Echo Land Trust. That includes a disc golf course they hope to have up this summer, as well as winter activities.

Shaun, who remembers his first home-kit batch as “drinkable but not great,” looks forward to finishing construction so that he can concentrate on making beer, saying, “I can’t wait to put the hammers down.”

Hard slog

Back at Funky Bow, Paul and Abraham Lorrain still work hard at keeping existing clients happy and pursuing new accounts, six years after they started out by “schlepping kegs” on Paul’s jeep and knocking on doors.

They’ve gone from producing 100 gallons a week in their first year to 2,200 gallons a week today. Every weekend in Lyman, they welcome hundreds of customers “from beer geeks to Budweiser drinkers” for a musical party atmosphere with pizza, beer, wine and cider. They do events from children’s birthdays to retirement parties of up to 100 people, charging $22 a head for a beer, salad and pizza. For those wanting to spend the night, Paul rents out on Airbnb a yurt that sleeps up to six. They also partner with restaurants and pubs that carry their beer, including for charity events.

They’ve grown the brand well beyond their own backyard, now distributing in four states — Maine, Rhode Island, New Hampshire and Massachusetts. In Maine, Paul says that Funky Bow can be found at “all Hannafords, Shaw’s, four Walmarts, some Targets and every mom-and-pop shop along the road you drive by.”

Asked what advice they’d give to someone starting in the business today, Paul blurts out “Don’t do it!” while Abraham speaks of the constant money worries in an increasingly competitive industry.

“If you could just get up and make beer in the morning,” he says, “that’s great.”

0 Comments