Processing Your Payment

Please do not leave this page until complete. This can take a few moments.

- News

-

Editions

View Digital Editions

Biweekly Issues

- December 1, 2025

- Nov. 17, 2025

- November 03, 2025

- October 20, 2025

- October 6, 2025

- September 22, 2025

- + More

Special Editions

- Lists

- Viewpoints

-

Our Events

Event Info

Award Honorees

- Calendar

- Biz Marketplace

UMaine’s 3D printed house withstands winter weather tests

Courtesy / UMaine

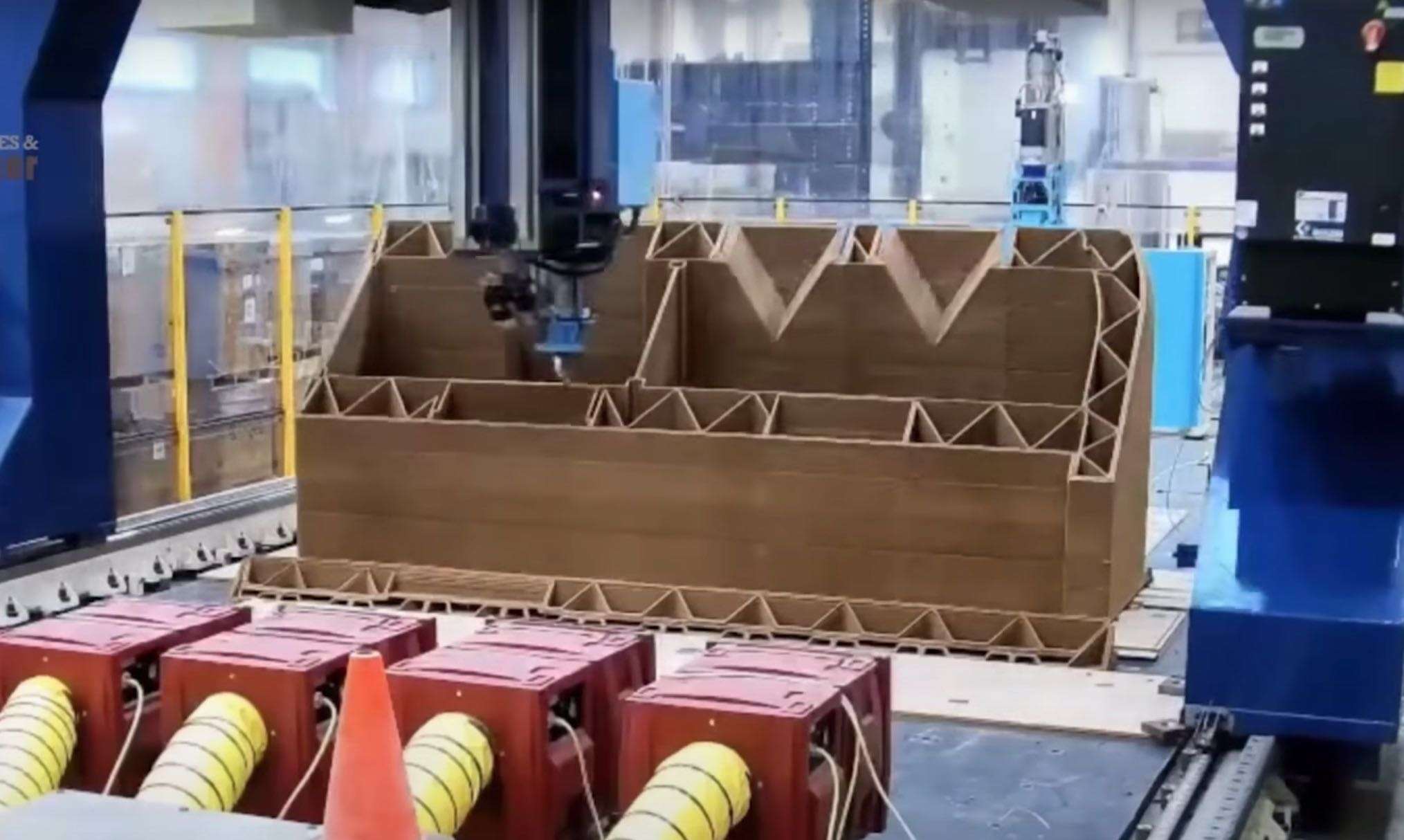

The flooring, walls and roof of this 600-square-foot prototype was created with wood fibers and bio-resins by a 3D printer.

Courtesy / UMaine

The flooring, walls and roof of this 600-square-foot prototype was created with wood fibers and bio-resins by a 3D printer.

Tests are underway on a house that was created with a 3D printer by the University of Maine.

At the same time, the university is collaborating with a Bangor nonprofit to create a first-in-the-nation bio-based 3D-printed neighborhood in greater Bangor.

The prototype made of four modules has withstood both high winds and a snow load after being trucked to a concrete foundation outside the lab at the University of Maine Advanced Structures and Composites Center.

“It held up very well,” said Habib Dagher, the center’s founding executive director, who recently gave an update on what the center is calling BioHome3D.

The structure is designed to meet all building code requirements and stood fast against a major windstorm a month ago. The roof has been holding up to a significant snow load, Dagher said.

The prototype was equipped with sensors for thermal, environmental and structural monitoring to test how it performs through the winter. Researchers expect to use the data to improve future designs.

48-hour prints

The 600-square-foot prototype has 3D-printed flooring, walls and a roof made of wood fibers and bio-resins. Dagher said he envisions using those materials in the manufacturing process to quickly and efficiently create affordable housing.

“The goal is to print homes like this every 48 hours,” he said.

The four modules were assembled in half a day. Electricity was running within two hours.

The center unveiled BioHome3D last November. It was developed with funding from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Hub and Spoke program between the UMaine and Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Partners included MaineHousing and the Maine Technology Institute.

The house is fully recyclable and highly insulated with 100% wood insulation. Construction waste was nearly eliminated due to the precision of the printing process.

The U.S., and Maine in particular, are experiencing a crisis-level shortage of affordable housing. The National Low Income Housing Coalition reports that nationally, there is a need for more than 7 million affordable housing units. In Maine, the deficit is 20,000 housing units and growing each year, according to the Maine Affordable Housing Coalition.

Nearly 60% of low-income renters in Maine spend more than half of their income on housing. The situation is exacerbated by the challenges of a labor shortage and supply chain-driven price increases for building materials.

3D manufacturing technology is seen as a way to address labor shortages and supply chain issues that are driving high costs and constricting the supply of affordable housing. The automated technology can be used to print modules at a manufacturing facility and then taken offsite for installation, said Dagher.

The process developed at UMaine allows homes to be customized to meet a homeowner’s space, energy efficiency and aesthetic preferences. And homebuyers can expect faster delivery schedules, he said.

Dagher noted that other technologies are being developed to print 3D homes, but most use concrete and only the concrete walls are printed to top a conventionally cast concrete foundation. Traditional wood framing or wood trusses are used to complete the roof.

Bio-print neighborhood

The University of Maine is collaborating with Bangor nonprofit Penquis and MaineHousing to create a first-in-the-nation bio-based 3D-printed neighborhood in greater Bangor, consisting of nine homes that are expected to provide housing for individuals experiencing or at risk of homelessness.

The project was recently awarded $3.3 million through congressionally directed spending and a $300,000 grant from the KeyBank Foundation’s National Community Benefits Plan. Penquis has also secured funding from NeighborWorks America, a congressionally chartered nonprofit that supports community development throughout the U.S.

Penquis is Maine’s largest community action agency serving primarily low- and moderate-income individuals in Penobscot, Piscataquis and Knox counties, with four focus areas: economic security, school readiness, reliable transportation and healthy lives.

Penquis’s director of housing development, Jason Bird, noted that Maine has an estimated shortage of 20,000 to 25,000 affordable rental units.

“One of the greatest challenges is the cost and slow pace of housing construction,” Bird said. “This project is investigating ways to create units more quickly and inexpensively, as well as more sustainably.”

The nine homes will be constructed in UMaine’s planned Factory of the Future laboratory over four years in phases, allowing time to evaluate and modify the home’s design, based on housing performance, cost and feedback from the homes’ occupants. The goal is to optimize the home’s design and minimize cost in order to make the new type of construction commercially viable.

Joan Ferrini-Mundy, president of the University of Maine and vice chancellor for research and innovation for the University of Maine System, said the neighborhood project will also provide students with immersive training internships at the intersection of engineering and computing.

The goal is to have homes available in about five years, said Dagher.

“We’re already learning a lot from the first home,” he added.

World’s largest printer

The center is home to the world’s largest 3D printer, manufactured by Ingersoll Machine Tools in Rockford, Ill., which was unveiled in 2019.

The massive printer can produce objects up to 100 feet long by 22 feet wide by 10 feet high.

To demonstrate its capabilities, the center, shortly before the unveiling, printed a 25-foot, 5,000-pound patrol boat over the course of three days and a 12-foot-long U.S. Army communications shelter.

The acquisition is designed to expand the potential of the 3D printing market and create a new market for Maine’s forest products.

The printer is expected to support several private, defense and infrastructure applications.

‘Factory of the future’

Dagher said the center will be able to scale its advanced manufacturing research in housing construction with the opening of the green engineering and materials research laboratory, which the center has dubbed “factory of the future.”

Plans for the lab were unveiled in 2021. The lab, estimated to be between 78,000 square feet and 92,000 square feet, will be connected to the current center.

The total cost of the expansion is estimated at $115 million.

“We’re at $80 million,” said Dagher.

That includes $25 million in direct investment, including $15 million through the Maine Jobs & Recovery Plan and $10 million in the FY22 federal budget. Nearly $40 million in other federal funds are pending for the project.

Designs for the factory of the future and its AI systems are underway, said Dagher.

The goal is to start construction of the facility in about a year.

When complete, the lab will serve as a hub for artificial-intelligence-enabled, large-scale digital hybrid manufacturing.

Trees and corn

The 3D printed house was built using pellets made from wood residuals from Maine forests and combined with bio-resin, then extruded through the printer layer by layer.

At one time, Dagher noted, waste from Maine’s sawmills went to the pulp and paper industry. That industry has scaled back.

“Now we have a glut of wood residuals from the sawmills,” he said. “So we grind it into powder and make it into pellets by combining with resin and put into 3D printer.”

A survey revealed that Maine produces about 1 million tons of wood residuals annually.

A 600-square-foot home uses 10 tons of that material. That means Maine produces enough wood residuals to build 100,000 homes that are 600 square foot each.

Aside from availability, another advantage is that residual material is cheaper than plywood and lumber, Dagher said.

The automated modular approach would allow printing to occur inside a manufacturing facility year-round, without being subject to the weather, he added.

The process allows the walls and roof to be printed with cavities that accommodate insulation, plumbing and wiring, which can also be installed in the factory.

Push-button design

Automation provides consumer opportunities for customization, he said

“Imagine a day, when you can sit at your computer screen, you can design the house, then push the button and say, ‘Order one,’” he said. “And it will be 3D printed and maybe in a week or two you can have delivery of your house, custom-designed to your needs.”

He continued, “We’re not there yet, but that’s where we’re heading. Imagine a day where we have factories like this that can produce these across the country. And we can take Maine-made wood pellets and ship them across the country to feed these factories.

The pellets can also be made in other places around the country where there are wood resources.”

The fiber doesn’t have to be wood, he noted. It can be agricultural waste, such as corn stalks, which the center is also experimenting with.

The bio-resin used to make the pellets are mostly derived from plant sugars, he said. The first house used corn sugar.

“That’s not necessarily where we’ll end up,” he said.

Given the organic nature of the material, a printed object can be ground up and the material used to print something else.

As a research and development project, printing the house started at 30 pounds of material extruded per hour. By the time it was finished, the team had scaled up the rate to 120 pounds per hour. A month ago, the center installed an extruder head that can print about 500 pounds per hour.

“It’s a game-changer,” he said.

As the project evolves, the goal is to get to 1,000 pounds per hour by having two extruder heads working together.

The first house weighs 40,000 pounds, so a rate of 1,000 pounds per hour means the print will take 40 hours.

“We’re not there yet by any means, but we’re inching up toward that goal,” Dagher said.

Another goal is to print the insulation and electric and plumbing conduits inside the house’s walls and roof as they’re being made.

Mainebiz web partners

Related Content

The Giving Guide

The Giving Guide helps nonprofits have the opportunity to showcase and differentiate their organizations so that businesses better understand how they can contribute to a nonprofit’s mission and work.

Learn More

Work for ME

Work for ME is a workforce development tool to help Maine’s employers target Maine’s emerging workforce. Work for ME highlights each industry, its impact on Maine’s economy, the jobs available to entry-level workers, the training and education needed to get a career started.

Learn More

Groundbreaking Maine

Whether you’re a developer, financer, architect, or industry enthusiast, Groundbreaking Maine is crafted to be your go-to source for valuable insights in Maine’s real estate and construction community.

Learn more-

The Giving Guide

The Giving Guide helps nonprofits have the opportunity to showcase and differentiate their organizations so that businesses better understand how they can contribute to a nonprofit’s mission and work.

-

Work for ME

Work for ME is a workforce development tool to help Maine’s employers target Maine’s emerging workforce. Work for ME highlights each industry, its impact on Maine’s economy, the jobs available to entry-level workers, the training and education needed to get a career started.

-

Groundbreaking Maine

Whether you’re a developer, financer, architect, or industry enthusiast, Groundbreaking Maine is crafted to be your go-to source for valuable insights in Maine’s real estate and construction community.

ABOUT

NEW ENGLAND BUSINESS MEDIA SITES

No articles left

Get access now

In order to use this feature, we need some information from you. You can also login or register for a free account.

By clicking submit you are agreeing to our cookie usage and Privacy Policy

Already have an account? Login

Already have an account? Login

Want to create an account? Register

Get access now

In order to use this feature, we need some information from you. You can also login or register for a free account.

By clicking submit you are agreeing to our cookie usage and Privacy Policy

Already have an account? Login

Already have an account? Login

Want to create an account? Register

0 Comments