Processing Your Payment

Please do not leave this page until complete. This can take a few moments.

UMaine team has created a statewide production hub for making critically needed PPE

Courtesy / University of Maine

Nick Hill, an engineering assistant, and Nayereh Dadoo, a staff chemist with the University of Maine’s Process Development Center, mix a batch of hand sanitizer, using alcohol sourced through a production chain of breweries and distilleries.

Courtesy / University of Maine

Nick Hill, an engineering assistant, and Nayereh Dadoo, a staff chemist with the University of Maine’s Process Development Center, mix a batch of hand sanitizer, using alcohol sourced through a production chain of breweries and distilleries.

A team put together by the University of Maine System to address the shortage of personal protective equipment for health care workers has facilitated production of hospital-grade hand sanitizer, face shields and intubation boxes.

Assembled in late March, the team has called on manufacturers, distilleries and breweries to help meet health care needs. As of late April, production has included 2,800 gallons of hand sanitizer, distributed to 51 hospitals and other health-related facilities; hundreds of intubation boxes and hundreds of thousands of face shields.

The team operates under the Maine Emergency Management Agency and includes UMaine, the Maine Department of Economic and Community Development, Maine Manufacturing Extension Partnership, MaineHealth, St. Joseph Hospital, Northern Light Health, Manufacturers Association of Maine and Maine Procurement Technical Assistance Center.

Initially focusing on hospital-grade hand sanitizer, UMaine’s Process Development Center and chemical and biomedical engineering faculty used existing supplies and Food and Drug Administration guidelines to produce 25 gallons.

Longstanding relationships

The center is UMaine’s commercial-scale pilot plant, established in 1987 to primarily support the pulp, paper and bioproducts sector with research, development, demonstration and commercialization services.

“A lot of our faculty have pretty active and longstanding interactions with folks in health care,” Michael Mason, a professor in the department of chemical and biomedical engineering, told Mainebiz.

The department has previously talked with Northern Light Health about ways to bring students into internships to investigate issues around sterilization, he said. That context brought Northern Light to the department to help address the sanitizer shortage.

“As early as March 18 or so, we started conversations about using equipment they had in the hospital to look at sterilizing masks, gowns, sheets, rooms, everything,” Mason said.

By March 20, Mason was connecting with other hospitals that would run out of sanitizer in a matter of days.

“It was time for us to act,” he said. “The first thing we needed to do was provide the process and understand the chemistry.”

The chemical engineering faculty met on a Sunday at UMaine’s Process Development Center. Using World Health Organization and FDA guidance, they mixed 25 gallons using existing materials. Central Maine Medical Center in Lewiston picked up that batch the same day.

Urgent need

The urgency was immediately evident. On a recent morning, Mason noted, he received 2,700 emails asking about hand sanitizer production.

“It became evident that this was well beyond our faculty working out of our building,” he said.

With Colleen Walker, director of the Process Development Center, the team worked on the problem of scaling up.

“We went from 25 gallons to needing 400 to 500 gallons per day to meet growing demand,” Mason said.

Within a day or two, the team began hearing through word of mouth many brewers and distilleries wanted to jump in.

“It became obvious that we needed to provide coordination," he explained, so that rather than one business creating a small amount of sanitizer, a production chain could be created to create large amounts.

Alcohol production

Walker started reaching to distilleries and breweries.

“The critical thing was getting enough alcohol,” she said.

The center began working with Maine Distillers Guild’s Ned Wight, who is coordinating alcohol supply. Brewers provide beer to the distilleries, and include familiar beer makers such as Allagash, Maine Beer, Rising Tide, Foundation, Oxbow, Shipyard, Baxter, Threshers and Tumbledown.

Walker’s center guided distilleries through the process of creating the high-purity alcohol that would be needed to create FDA- compliant 80% alcohol sanitizer.

The distilleries include New England Distilling, Hardshore Distilling, Stroudwater Distillery, Sebago Lake Distillery, Split Rock Distilling, Blue Barren Distillery, Mossy Ledge Spirits, Chadwick’s Craft Spirits, Wiggly Bridge Distillery, Round Turn Distilling, Three of Strong Spirits, Maine Craft Distillers and Boston Brands.

Walker worked with Mason and his team to make sure they had got the right chemicals to mix the sanitizer recipe.

The center also utilized the university’s transportation service to pick up alcohol from the distilleries and drop off sanitizer.

The center is now working in 50-gallon batches, Walker explained. It picks up the alcohol in barrels, adds hospital-grade peroxide and glycerol, mixes and packages it in 55-gallon barrels and in one- or five-gallon containers, she said. A 55-gallon batch can be made in 30 minutes.

The sanitizer is being produced in the center’s 500-square-foot wet lab by a three-person production team: two to produce and bottle, and one to move materials and supplies.

Nestlé is donating 0.5-liter bottles to help distribute hand sanitizer in smaller portions.

Recipients include Central Maine Medical Center, Northern Light, Covenant Health, MaineHealth, Cary Medical Center, Houlton Regional Hospital, Down East Community Hospital, Maliseet Health and Wellness Center and Dorothea Dix Psychiatric Hospital.

Fast turnarounds

Mason said his team’s role shifted as the faculty became an information hub for hospitals and other first responders, the state and industry.

“It quickly became obvious that we needed to organize as a group to tackle multiple problems within some structure,” he said.

Researchers in UMaine’s chemical and biomedical engineering department have evaluated sterilization technologies and techniques, conducted scientific literature searches on the performance and effectiveness of techniques, and documented protocols of other hospitals and medical users. They compiled information allows health care providers to develop protocols specific to their institution and guidance on equipment to acquire. They are consulting directly with Maine hospitals as protocols are being evaluated.

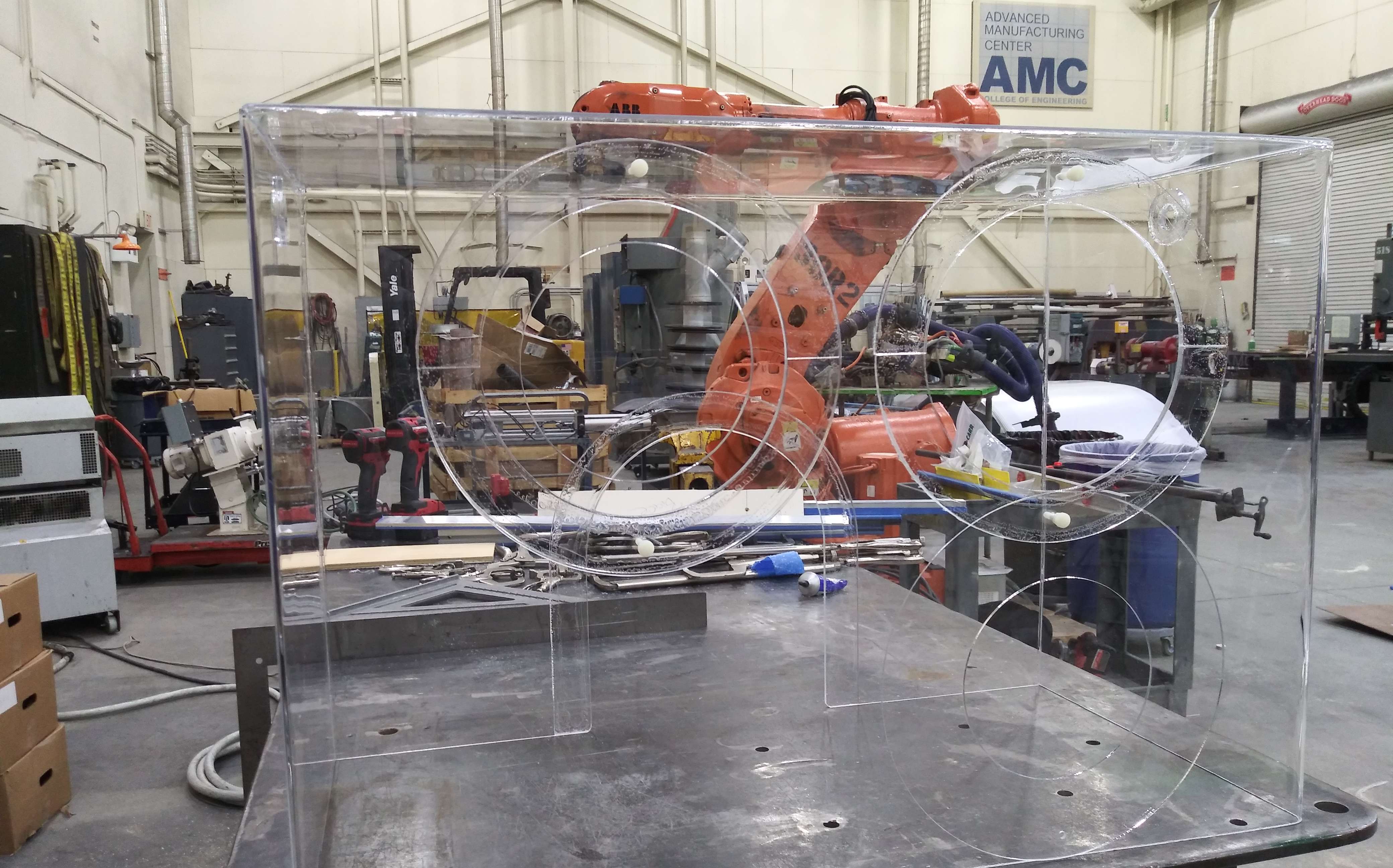

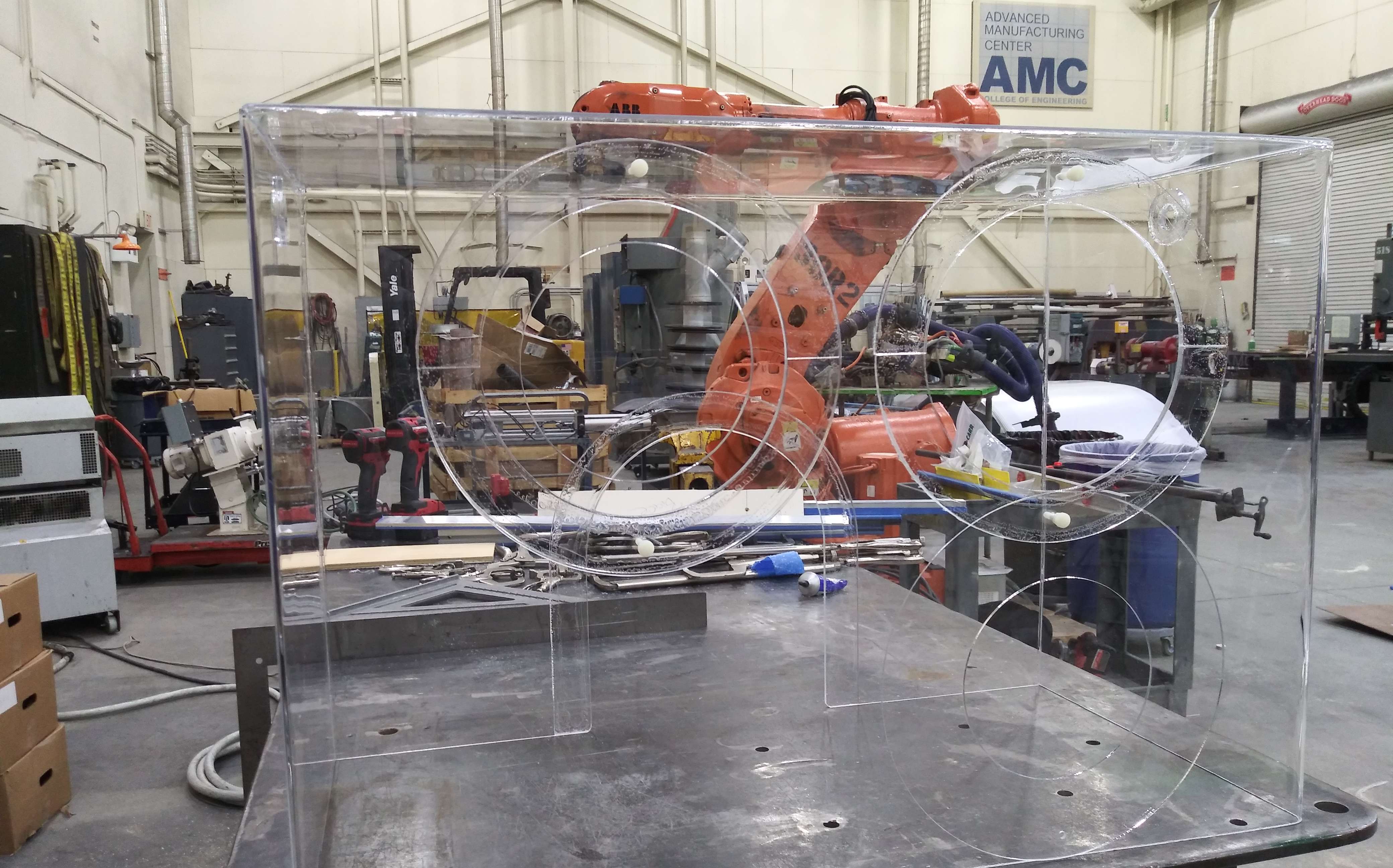

UMaine’s Advanced Manufacturing Center, on the Orono campus, worked with hospitals to develop prototypes of intubation boxes and face shields.

An intubation box is a three-sided shield with handholes that covers the patient’s head and shoulders, and allows medical personnel to intubate safely to contain aerosol spray.

Like the hand sanitizer, development of the intubation box prototype also occurred in a short time, said John Karp, a business growth coach at Maine MEP.

Karp said he was contacted on a Sunday afternoon by a medical provider, who emailed information about an intubation box developed by a doctor in Taiwan.

“I made a hand sketch, took a picture, texted it to John Belding [director of the Advanced Manufacturing Center], who drew it up on CAD, and I called a buddy who’s got a machine shop,” Karp described.

By 9 a.m. the next morning, the prototype was built. Karp’s wife picked it up and brought it to Maine Medical Center for evaluation.

“By 5 p.m., we had feedback on the modifications they needed dimensionally, which I fed up to John Belding,” who modified the drawings and sent them back to the machine shop, which had the final product in production by the end of the week.

Moving target

The team has also been coordinating with cut-and-sew manufacturers to produce non-medical cloth face coverings, said Larry Robinson, president of the Maine Manufacturing Extension Partnership.

“We knew they had the processing capacity," he said.

Maine MEP is now working on that initiative with over three dozen manufacturers at various levels of production, he said. They range from one-person shops to L.L. Bean Inc., which is making tens of thousands of face coverings.

“We’re continually reaching out to companies,” said Robinson.

Other initiatives include testing N95 masks, typically single-use masks, before and after sterilization treatments to ensure the filtering performance has not been degraded. 3D printing is being evaluated as a tool to help with PPE production and prototyping.

The team, Maine MEP, and representatives from Maine’s medical centers and the Maine Department of Economic and Community Development have been cataloging needs from hospitals and medical centers, and collecting information worldwide to vet innovations.

The team evaluates evolving health care guidance and hospital practices, along with tightening supply chains, and provides a continual conduit of information to manufacturers, said Jake Ward, UMaine’s vice president for innovation and economic development.

Throughout, the team has continually pivoted to keep up with shifting demand.

“That’s a moving target,” said Mason.

Lessons learned

The urgency of the situation has resulted in lessons that can be carried forward into the future, Ward said.

“Maine is a tight community and really stands up,” he said. “We need to know what our local supply chain is. We have to be less reliant on national and global supply lines that caused this collapse in all sectors. We got so used to this ‘just in time’ mentality. That in itself creates some of the challenges in the supply chain. You used to have a warehouse of supplies and now you’re just getting a load every week. I think we need to think about how to manage within that system a bit differently”

Mason noted that, from the research point of view, the team network helped to define and address problems quickly, in a matter of hours rather than months or years.

Existing relationships between sectors have been essential for ramping up production, noted Robinson.

“Manufacturing is important to the country to be able to produce what we truly need in an emergency like this,” he said. “Because we’re a small state, we’re able to leverage a lot of relationships.”

0 Comments