Processing Your Payment

Please do not leave this page until complete. This can take a few moments.

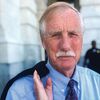

Exit focus: The good, the bad and the unnerving about selling a family business in Maine

Photo / Jim Neuger

Celine and John Goodine, owners of Elm City Photo, are seeking a buyer for the Waterville business founded by John’s parents in 1946.

Photo / Jim Neuger

Celine and John Goodine, owners of Elm City Photo, are seeking a buyer for the Waterville business founded by John’s parents in 1946.

At Elm City Photo in Waterville, John and Celine Goodine run a second-generation business without a third-generation succession plan.

The company’s roots go back to World War II, when John’s mother Dorothy developed photos in the home bathtub for customers to mail overseas while her husband Leroy served in the military. During the war he was stationed in Pensacola, Fla., and then Hilo, Hawaii, to work in the Navy photo lab.

When the war was winding down, he was assigned to take photos of USO performers entertaining the troops. The couple started Elm City Photo in 1946 as a wholesale operation developing pictures for local drugstores.

Today with just one employee on staff, the Goodines offer services from scanning to archiving. Just as they help customers preserve family histories by digitizing photos and videos, they’re seeking a buyer to carry on the legacy of the business and maybe take it in a new direction.

“We’re in our 70s and have a great business that we’d love to see go to someone else,” says John, a Navy veteran like his father who enlisted in 1967 right after high school. Elm City Photo “is profitable, it’s clean, it’s environmentally sound and it’s turnkey,” meaning that a new owner “wouldn’t have to pick up somebody else’s mess,” he says.

On a more personal note, Celine is hoping for a like-minded owner who prizes customer interaction as much as she does, holding a hand or offering a hug when they’re having a rough day.

“It’s hard to find that person in this modern-day world,” she admits.

In a state where an estimated 80% of businesses are family-owned, exit planning is a must. Business survival rates thin out with each generation, as reflected in oft-cited statistics that 30% of family businesses successfully transition to the second generation, 13% advance to the third and only 3% make it to the fourth generation.

While large, multigenerational companies like Hussey Seating and L.L.Bean tout their deep roots, many of their smaller peers without guaranteed family succession face an uphill battle finding the right buyer. That includes the Goodines, whose four children grew up helping out but have all pursued different professions.

‘Seller’s market’ but lower multiples

Broadly speaking, a family business is one in which two or more family members — joined by marriage or blood — hold majority ownership or control. Many belong to the Institute for Family-Owned Business, a Portland-based nonprofit trade group with regular sessions and resources on succession planning for close to 200 members.

“You can’t get somewhere if you don’t have a plan or road map,” says Catherine Wygant Fossett, the group’s executive director. “And you certainly can’t get off the highway smoothly unless you know your exit.”

Those that have sold their businesses know the road is anything but smooth, requiring a combination of patience, emotional stamina and an understanding of market conditions.

Recent transactions include the sales of Tiny Homes of Maine, a first-generation business that was acquired by Hancock Lumber; and H.A. Mapes, a third-generation, Springvale-based fuel distributor and convenience-store operator acquired by Nouria Energy Retail Inc. in 2023.

For those who have yet to take the plunge, market conditions appear to be mostly favorable.

“It’s still a seller’s market, but the multiples and valuations aren’t as robust,” says Jeff Tounge, a Portland-based sell-side adviser to companies in the lower and middle market.

“Strategic buyers in various industries are looking to grow, and you can only grow so fast with organic growth so they’re looking to acquisitions. There’s still a lot of that going on.”

As for what’s likely to get buyers’ attention, David Jean, director of Altus Exit Strategies LLC in Portland, notes that companies with a robust business model tend to be the most attractive.

“The more families run their business like a business, the better they fare,” he says. Less enthusiastic about smaller operations like mom-and-pop stores, he warns that “if you have an owner that can’t take more than a week off, that’s not a business. That’s just a job.”

He recommends exit planning as early as possible, adding that “you should always be thinking about reducing risk and trying to do whatever you can to maximize value.”

Playing the long game

Sometimes the longer a business has been around, the longer the timetable for a sale. For H.A. Mapes, it took multiple steps to cross the finish line.

Henry Allen Mapes founded the company in 1936, to deliver heating oil to local customers. His son Harry joined in 1950 and led expansion across southern Maine. Harry’s son, Jonathan Mapes, who grew up emptying ashtrays from offices and driving the oil truck in high school, formally joined the business in 1982 and built the fuel distribution division. He sold the heating oil business in 2004 and started adding convenience stores in 2018.

Realizing the need for a partner with expertise in running the stores, In 2019, Mapes hired Matrix Capital Markets Group Inc., an independent investment bank, to explore a potential sale of the company and identify any shortcomings from a buyer’s perspective.

After implementing some of Matrix’s recommendations, Mapes went back to Matrix in 2022 to prepare a sale of the company, which had grown to around 130 employees and more than a dozen retail locations.

Out of 30 potential suitors who received the initial pitch deck, 10 expressed interest in proceeding and three made the final round. In August 2023, Nouria Energy Retail, a division of Worcester, Mass.-based Nouria Energy Corp., agreed to buy the operating assets of H.A. Mapes for a multiple that Jonathan Mapes said exceeded his expectations.

“It was a great run, it was a great name, and we had nice conclusion to the play — it was a fitting ending,” he says.

The final act followed a lot of sleepless nights, especially in March 2023 when the Silicon Valley Bank collapse rattled financial markets and sparked concerns about the health of the banking sector.

He also found it difficult not being able to tell employees about the planned sale until about 60 days before it was completed and tried to keep his cool throughout.

“Like the old anti-perspirant commercial says, you can’t let them see you sweat.”

Frustrated with the length of time it took to complete the deal, he never thought of stopping. Nor did his CFO Steven McGrath, who now works as a consultant providing corporate and financial management advice.

“Part of it was us needing to build certain aspects, and part of it was you can’t just show up and say, ‘I want to sell my business today,’” McGrath explains. “The buyers come in, and they have their own timetables. We had a buyer who took their sweet time closing.”

Mapes, 65, recently bought a farm — no animals, just land and buildings — and is plotting his next move, perhaps teaming up with a developer on housing.

“I didn’t sell the business to retire,” Mapes says. “I sold the business.” To current family business owners mulling a sale, he says, “Stay calm and let your ego get out of the way … You’re never as important as you think you are.”

Growing new roots in Gorham

Like Mapes, Jeff O’Donal found selling his business to be somewhat frustrating. He bought O’Donal’s Nursery in Gorham from his parents in 2006, decades after they had bought the business from the Jackson family who started the original firm in Portland in 1850.

After hearing from a grocery store owner who had successfully sold his business to employees, O’Donal opted to go the same route, turning to Rob Brown, a Northport-based adviser with the nonprofit Cooperative Development Institute, to help organize a worker cooperative buyout.

“I had every intention of staying on a member and working part-time, but in the end they told me no and I was made a non-entity,” says O’Donal, who nevertheless has no regrets about selling to former employees who helped build the business.

While initially told the sale would take six months to a year, it dragged on for 18 months and was “far more complicated than I wanted it to be,” says O’Donal, who sold the operational assets but kept the land.

Now the 67-year-old breeds day lilies in Maine and New Hampshire, where he runs a nursery in Conway he bought a few years before O’Donal’s Nursery and Garden Center became an employee-owned cooperative in 2023.

“It should have gone quicker and had more money, but when you’re selling to employees you’re not going to get top dollar,” he says.

Unexpected path

Some business owners have even less time to play with. That was the case for Corinne and Tom Watson, who envisioned Tiny Homes of Maine as a long-term investment when they started in Houlton in 2016. The couple, who are in their 40s, designs and builds compact abodes on wheels designed to withstand harsh New England winters.

“We had planned to grow the business until retirement or initially pass it down to one of our three children,” says Corinne, who was honored on the Mainebiz Next list in 2020.

After navigating regulatory hurdles, the passage of two laws related to tiny homes in Maine, and the pandemic, the couple faced their most difficult test in September 2023 — a fire in 2023 that destroyed leased space where homes were being manufactured. That slowed but didn’t stop orders from being delivered.

“These experiences have toughened us, but they also made us reflect on the future and recognize that, while we loved the business, we had become open to new opportunities,” Corinne Watson says.

An unexpected opportunity arose after the fire, when Kevin Hancock of Hancock Lumber got in touch offering encouragement, which led to deeper discussions about the housing crisis and challenges in the conventional building industry.

“Through several Zoom meetings and in-person visits, we discovered a shared vision for Tiny Homes of Maine,” Corinne Watson says, prompting the couple to agree to sell the business to Hancock Lumber in a deal that closed in late October.

While financial terms were not disclosed, Watson said that she and her husband sought advice from mentors and business advisers on valuing their business and were satisfied with the outcome.

Under the new ownership, the Watsons plan to stay on indefinitely, with Corinne as general manager and her husband as a designer and operations manager. They also hope to take their first vacation in several years.

Back at Elm City Photo in Waterville, the Goodines — former hippies who traveled around the country in a Volkswagen bus for a year before getting married — are giving themselves about a year and a half to land a suitor for their business.

Hesitant to hire a broker, they have begun putting out feelers and letting customers know about their plans in case there’s any interest.

“We aren’t looking to travel around the world — our focus is on our family and our lives together,” says Celine. “We have our health, and we want to have time together.”

In the meantime, they’ve still got photos to print and a business to run.

0 Comments