Processing Your Payment

Please do not leave this page until complete. This can take a few moments.

Maine's mix of colleges and universities have created an 'education hub'

Laurie Lachance admits that, until recently, she never expected to end up serving as a college president — though her background provides a unique perspective on what Maine higher education was, is, and could be in the years to come.

An economist by training, Lachance spent a decade with Central Maine Power, then served as state economist from 1993-2004, spanning three administrations, those of Gov. John McKernan, Gov. Angus King and Gov. John Baldacci. From there, she became executive director of the Maine Development Foundation, a state-chartered non-profit that attempts to get government and business working together to strengthen the Maine economy.

It was then that Lachance focused her research skills on higher education and also began serving on college and university boards, first at the Margaret Chase Smith Policy Center at the University of Maine and Muskie School of Public Service at the University of Southern Maine, and later the University of Maine Board of Visitors and Thomas College.

Thomas, a business and liberal arts school in Waterville, was looking for a new president in 2012, and identified six finalists. Someone contacted for a reference check asked whether Lachance was being considered. The search committee then asked her if she'd be willing to apply. One interview later, she was offered the job.

“This is a board of self-made businesspeople,” Lachance says. “When they make a decision, they don't waste any time implementing it.”

Lachance took over at a moment when Thomas was embarking on significant expansion. This summer, a new academic building funded by the Harold Alfond Foundation is going up, along with a residence hall to accommodate growing enrollment. Two-thirds of students now live on campus, even though many also work other jobs while studying. Thomas has 800 full-time and 200 part-time students, by far the most in its 120-year history.

Lachance was the first Thomas alumnus to serve as president — she earned her master's degree there — and is also unusual in not holding a Ph.D.

“I wasn't looking for a change,” Lachance says, “but now I feel this is where I was meant to be.”

Her approach to college administration is informed by the research she's done for decades. “There are many important factors in creating economic development on a statewide basis, which was our mission at [Maine Development Foundation],” she says.

While preparing a paper called “In Search of Silver Buckshot,” she concluded there was no silver bullet, no single factor to guarantee long-term economic success. “Infrastructure, energy costs, taxation are important, but not determinative,” she says.

Later, though, in preparing a series in cooperation with the Maine State Chamber of Commerce called “Maine's Investment Imperative,” she says, “It just hit me that we could get everything else right but we would still not get to prosperity unless every Maine person is working to their full potential.”

And that means more investment, and not just financial investment, in higher education.

In one sense, the landscape is bleak. Lachance says students and their parents are skeptical about the value of higher education, even as everything indicates that Maine's shift, first from a manufacturing to a service economy and then to a knowledge economy, will continue.

The baby boom initially bolstered Maine's demographics, “but now it's crashing,” she says, with Maine now the nation's oldest state, including a particularly small cohort of traditional college-age students.

The economic situation is “very challenging,” she says, with wages stagnating or declining, while college costs continue to rise. This leads some potential students to say, “This is crazy. It's not worth it,” she says.

She understands many are “disillusioned and angry,” particularly since today's students are burdened by what she calls “an obscene” level of loan debt, over $1 trillion nationally. Colleges themselves, including USM, have had their own debt issues.

Finally, technology has “really disrupted the model of higher education,” with some schools handling the transition better than others.

Still, Lachance says this is a time of opportunity for higher education, and that the institutions that will thrive will learn from current problems and craft solutions.

For instance, Thomas' growth has been fueled in large part by its diversification from traditional business courses into majors that can be categorized as “practical” liberal arts. While liberal arts offerings, in general, do not have “as clear a connection to jobs” as technical classes, Lachance believes they are vital to creating a full set of skills for graduates.

One of her first moves at Thomas was expanding a program for incoming freshman that takes place two weeks before other students return. If offers intensive, one-on-one tutoring and mentoring, with the college's best teachers, and also takes students through an entire semester class, including evening and weekend sessions.

“Once you have a college course under your belt, it's a lot more likely you'll succeed in your first year,” she says.

Ultimately, Lachance would like to offer this opportunity to every undergraduate.

The trustees have also approved beefing up the job guarantee the college has offered for a decade. If a graduate is unable to find a suitable job, tuition will be refunded — something Thomas hasn't yet had to do.

The offer comes with strings attached. Students have to maintain a certain grade point average, do community service, and participate in campus activities.

And the college strives, through the orientation program and many classes, to provide the “softer skills” businesses need — oral and written communication, public speaking, team building.

Online learning is provided, but usually as an extension of on-campus classes, providing flexibility students need to juggle college, work and family. Lachance says digital education won't replace classroom teaching, at least for undergraduates.

By reliably creating value for students, colleges and universities can overcome the disillusionment the prolonged economic downturn has created, she says.

Thinking larger, Lachance says Maine has a real chance to become an “education destination” different from those represented by such traditional education hubs as, say, Boston.

“Security and safety is such a big issue,” she says. “Look at the number of summer camps in Maine. If parents trust us to take care of our children, why shouldn't it work for higher education?”

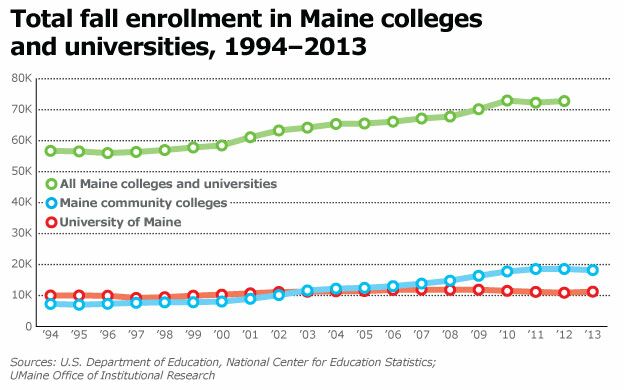

She says Maine has an unusually good mix of offerings, too. There's the state university system and community colleges, “which will continue to educate the largest number of students;” elite colleges such as the “little Ivies,” Colby, Bates and Bowdoin; specialty schools emphasizing the environment, Unity College and College of the Atlantic; and “practical” institutions emphasizing trades and professions — Thomas, St. Joseph's and University of New England.

“There's really tremendous diversity and choice here, something for almost every student,” she says. “We just have to embrace the idea that we can collaborate and not just compete.”

She admits there are challenges ahead. Legislators and governors must recognize that without more investment in the university and colleges, Maine won't get where it needs to go.

She's heartened, though, by a new group of college presidents prepared to innovate, mentioning Danielle Ripich at the University of New England and Susan Hunter, who's just assumed the helm at the University of Maine in Orono. Lachance also praised the appointment of David Flanagan as interim president at the University of Southern Maine: “He understands the whole system, and what it will take to change it.”

Lachance returns to her theme that, “In the knowledge economy, there is no greater resource than a skilled and educated workforce.” And in assessing Maine's place in the wider world, she endorses research that finds prosperity linked, not to geography, natural resources, or history, but to another factor bred through learning:

“The greatest determinant of future well-being,” she says, “is the capacity for innovation.”

Read more

'He wheeled and dealed': An interview with Mainebiz founder Jon Whitney

Mergers and regulations: Two decades of change in banking

Health care crossroads: Rising costs coupled with need to be affordable

Oil, propane expected to remain stalwarts as Mainers try new energy sources

Growth engine: Faster broadband seen as essential for Maine's economy

Forest products industry puts $8 billion into Maine's economy

Know your farmer: Locally sourced food trend buoys Maine farms

An industry, changed but still viable: One man's tale of Maine manufacturing

Groundfishing aground? The rise and fall of Maine's offshore fishing industry

Decades of tide changes: Investments help Bath Iron Works maintain its shipbuilding prowess

Reflecting on 20 years: Other 20-year-old companies look back

Mainebiz presents a 20-year retrospective of doing business in Maine

Comments