Processing Your Payment

Please do not leave this page until complete. This can take a few moments.

Baby, it's cold inside: $56M waterfront facility is poised to turn Portland into regional logistics hub

Photo / Jim Neuger

Eivind Dueland of Amber Infrastructure in the refrigerated storage section of the Maine International Cold Storage Facility in Portland, which is kept at −10°F.

Photo / Jim Neuger

Eivind Dueland of Amber Infrastructure in the refrigerated storage section of the Maine International Cold Storage Facility in Portland, which is kept at −10°F.

Inside the hulking white box of a building on the deep blue shores of Portland’s western waterfront is a 106,000-square-foot logistics universe waiting to be filled.

Weeks before the long-awaited opening of the $56 million Maine International Cold Storage Facility, workers in dark insulated suits are putting the finishing touches on the loading dock and in the supersized freezer. Floor-to-ceiling metal racks as far as the eye can see give the cavernous space a surreal feel, a bit like the warehouse at the end of the 1981 film “Raiders of the Lost Ark” except that the Portland site was still empty when Mainebiz toured it with the developer ahead of the Feb. 3 opening.

More than decade in the making, the Maine International Cold Storage Facility marks a new chapter for Portland — and Maine — just as the U.S. cold storage market is taking off.

Over the next five years, analysts at San Francisco-based Grandview Research predict 16.3% compound annual growth in the U.S. cold storage market to $102.8 billion in revenue by 2030, amid increasing demand for fresh and frozen food products. The boom in online grocery shopping and a growing need for efficient supply chain management are contributing factors.

While Portland is one of the smaller U.S. markets, it is poised to punch above its weight as a regional logistics hub for seafood, produce, food and beverage products and biopharmaceuticals that need to be stored and transported at super-cryogenic temperatures.

“It is more than just a cold storage facility,” says Amir Mousavian, an associate dean and supply chain management professor at the University of New England. “It has the potential to serve as a pivotal asset that will reshape Portland’s economic landscape, bolster its logistics and supply chain capabilities, and drive sustainable growth for years to come.”

Economic impact

In 2017, researchers at the University of Southern Maine estimated the long-term economic impact of a cold storage warehouse at up to $900 million.

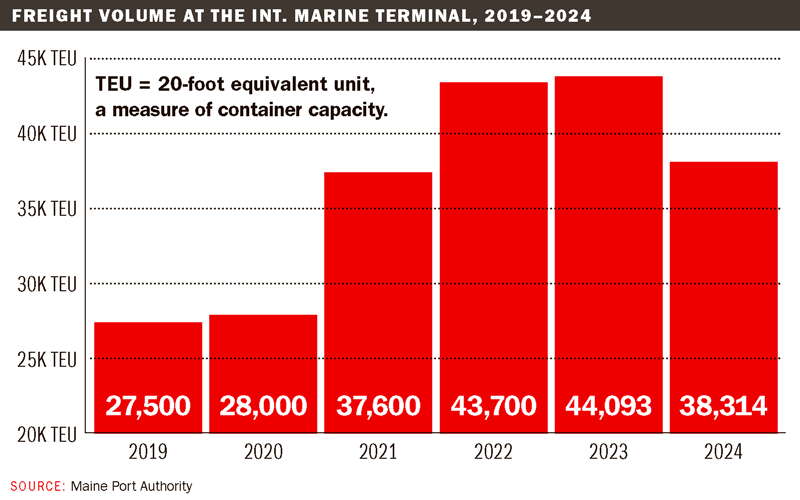

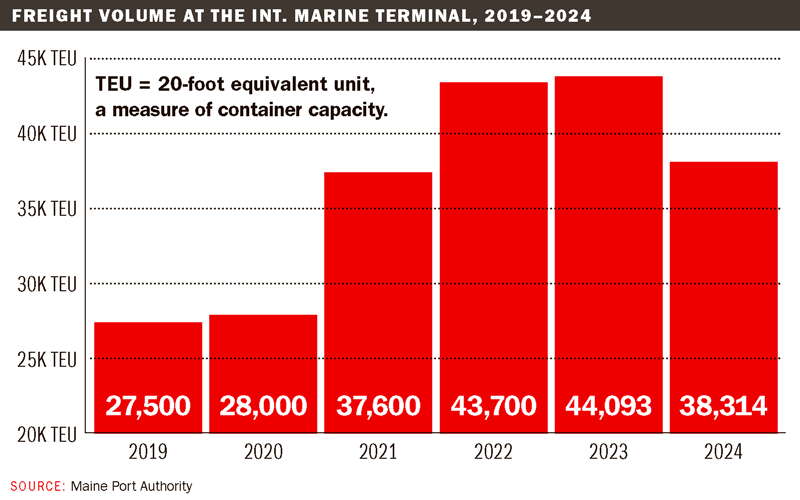

The port has gotten busier since then. Freight comes through the International Marine Terminal, which is anchored by Eimskip and handled a record 44,093 twenty-foot equivalent units — a measure of container capacity — in 2023. (See chart below.)

Although volume slipped to 38,314 TEUs in 2024, it is still well above pre-pandemic levels and expected to grow as the new cold storage hub complements operations. To prepare for the increase, the MPA and MaineDOT plan to use $17.8 million in federal funds to upgrade refrigerated container plug capacity at the marine terminal.

Bumps and starts

While Portland was home to at least two wharf-side cold storage businesses in the early 1900s, plans for a modern facility were sparked by the 2013 arrival of Eimskip USA, an Icelandic-owned shipping and logistics firm that revived container shipping at the IMT.

In 2014, the MaineDOT paid $8.5 million for a neglected property west of the Casco Bay Bridge that was home to the Portland Gas Light Co. from 1852 to 1965, and launched a competitive bidding process to select a developer for a waterfront warehouse.

While Eimksip was awarded building development rights in 2015, Atlanta-based Americold beat out a rival bidder to design and build a facility with a $50 million investment pledge.

The plan was for Americold to lease the site with Eimskip as the anchor tenant of a 68-foot-tall structure, prompting criticism from West End residents over exceeding the port development zone’s 45-foot height limit that some feared would impede their harbor views.

While a zoning change approved by the City Council in September 2017 cleared the way for Americold, the company abruptly retreated in June 2018, saying the expected operating cost did not meet its underwriting criteria.

Plan B

Moving ahead without Americold, the Maine Port Authority embarked on a $600,000 mainly federally funded cleanup to ready the site for development and worked to assemble a new consortium. Led by Eimskip, the group included Yarmouth-based Treadwell Franklin Infrastructure and U.K.-based Amber Infrastructure. They submitted a revised building plan in February 2020, which was approved by the City Council eight months later. At the start of the pandemic in March, the construction cost was estimated at $25 million to $38 million.

Fast forward to August 2022, when shovels went into the ground on a much pricier undertaking. Itasca, Ill.-based FCL Builders completed construction last month, with Amber Infrastructure as the sole owner and equity investor in a facility operated by Taylor Logistics Inc., an Ohio-based family-owned firm. The 106,000-square-foot facility boasts 21,000 pallet positions, 85,500 square feet of storage and more than 13 loading dock bays connected to the marine termina via a private road. Taylor Logistics’ value-added services range from transportation management to “case-picking,” which entails selecting individual cases or cartons to ship as a combined unit.

“Everybody assumes that it’s only storage, but really, it’s logistics,” Eivind Dueland, a senior vice president at Amber Infrastructure, says during an interview in the room-temperature office section of the building. “To be successful, this facility is not about bringing in product and then moving it out after a year. It’s about moving product through the facility — and by making transportation of that product more efficient for our customers.”

While Amber won’t have a hand in the day-to-day operations, it has a 30-year lease agreement with the Maine Port Authority that can be extended up to 50 years.

“We’re not a typical real estate investor that buys, develops and quickly flips the property,” Dueland says. “We are an infrastructure investor with a long-term time horizon.”

Taylor Logistics expects to employ more than 20 people at the facility, according to Will Roberson, the company’s president. Customers are lined up from Day One, he notes, without disclosing who and how many – only that it “won’t be an overwhelming number.”

The intention, he says, is to “ramp it up” in a smart and purposeful way.

As it does so, Jasper Wyman & Son, a Milbridge-based producer of wild blueberries and blueberry products, will be watching to see how things evolve.

While the company has no plans for now to use the facility, “the additional cold storage in Portland is a great option, and one that we would consider for the future if it makes sense for our business,” says spokeswoman Colleen Craig.

High expectations

The facility would bring more international business to the International Marine Terminal.

“Until now, the available cold storage options have predominantly been out of state, meaning that anyone looking to ship frozen goods internationally, to and from Portland, has had to factor in significant drayage [additional transportation] costs to access storage,” says Chelsea Pettingill, interim executive director of the Maine Port Authority. For many shippers, this has often meant it was more economical to use ports like Boston and New York and New Jersey.

Strategically located close to Maine’s two highways, the Portland International Jetport as well as a rail spur connecting into CSX’s North American rail network, the new facility “creates a hub with a variety of transportation options,” she says.

Eimskip, which reports “good volume” this year on its Green Line transatlantic route, anticipates benefits for both its European customers able to store frozen imports in Portland for U.S. distribution as well as export containers that get shipped overseas.

“This new cold storage can only grow our business,” says Gylfi Sigfússon, president and CEO of Eimskip USA. He looks forward to drumming up more business next month from European visitors coming for the Boston Seafood Show. Without naming names, he says they’re “interested in ocean transportation, storage and distribution opportunities to and from the IMT.”

It’s not just big corporate enterprises that are expected to use the new warehouse and distribution center, but also smaller businesses seeking to lower costs, according to Janine Bisaillon-Cary, Maine’s former top foreign trade official now leading a food-business accelerator program at the Maine Center for Entrepreneurs.

“This development offers Maine food producers and seafood companies from both local and rural communities a valuable chance to reduce expenses on trucking, storage and drayage, especially during a period of rising costs,” she says.

Seafood — mainly fish — will, in fact, be one of the first large-scale products inside the new facility, along with dairy, and then fruit and vegetables shortly after that. Even if they’re sourced from all of Maine’s 7,000-plus farms, there’s no shortage of space.

0 Comments